Why this topic matters in today’s exams

You know, there’s a pattern we see over and over again in India’s competitive exams. Talented students—those who read regularly, really grasp concepts, and can articulate their thoughts clearly in discussions—often leave the exam halls feeling uncertain. It’s not that they’re unsure about the facts, but they’re uneasy about how they performed.

This feeling of not being fully prepared isn’t always because they didn’t try hard enough. In fact, it often hits students who have done everything right by traditional standards. They’ve covered the material, they’ve revised, they’ve practiced. Yet, something still feels off.

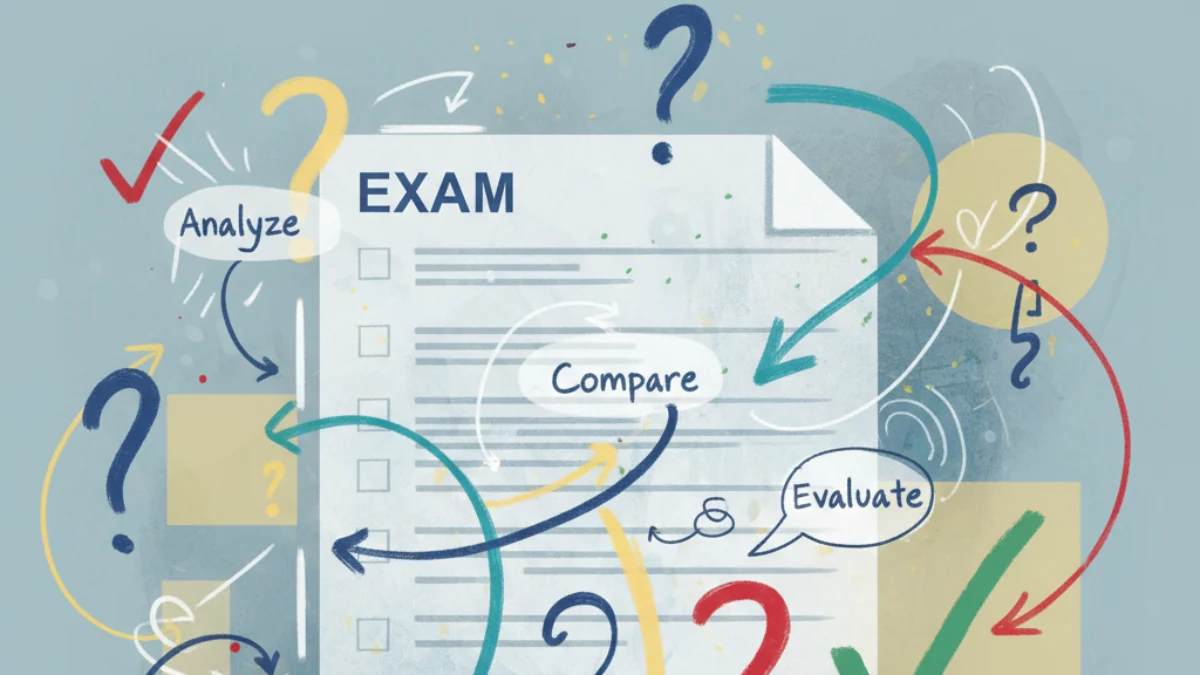

This is important because modern exams are changing in subtle but significant ways. Questions are increasingly designed to test how well candidates can process information, rather than just how much they can remember. The discussions around education, governance, technology, and society have also become more complex. Examiners are responding by framing questions that reward prioritisation, judgment, and relevance.

Students struggle with this not because they’re careless, but because their preparation often focuses on accumulating more notes, more sources, and more practice, while the exams are increasingly rewarding the ability to select and frame information effectively. This mismatch creates a persistent feeling that something is missing.

So, feeling underprepared isn’t always a sign that you didn’t study enough. Often, it’s a sign that your approach isn’t quite aligned with what the exam is looking for.

How examiners actually think about this area

To really grasp why smart students sometimes feel unprepared, it’s helpful to switch perspectives and see things from the examiner’s point of view. Examiners aren’t setting out to trick students; they’re trying to distinguish between candidates who have a similar level of knowledge. The real test isn’t just about what you know, but how you use that knowledge when you’re under pressure.

When crafting a question, examiners typically consider:

– What kind of judgment is this situation asking for?

– Which ideas are most important, and which just support those main points?

– How can a candidate show they understand clearly without getting bogged down in unnecessary details?

This is why questions are often designed to allow for multiple valid approaches, yet still narrow enough to penalize answers that wander off-topic. From an examiner’s perspective, an answer that tries to cover “everything related” often shows a lack of focus, not a deep understanding.

The way answers are evaluated usually follows certain patterns, like:

– Is the candidate addressing the main point of the question?

– Does the answer show awareness of the context and any limitations?

– Are the key points organized by importance rather than just in chronological order?

Talented students sometimes don’t fully appreciate this evaluation process. They might think that showing they know the material is enough to prove they understand it. But examiners are really looking for how well students can make decisions under pressure—what information they choose to include, what they leave out, and how they structure their ideas.

How the same concept appears across different papers

The feeling of being underprepared often intensifies because the same underlying skill is tested in very different formats.

Essay-style questions

The real difficulty here isn’t about knowing the material; it’s about how you present your ideas. Examiners want to see a clear and logical flow of thought. Even bright students who grasp many different aspects can find it hard to pick just two or three points that actually answer the question. Trying to cover too much ground can actually end up hurting their performance.

Objective or short-answer formats

Even when the answers are short, it’s really important to understand what the examiner is looking for. The choices given are set up so that being exact and understanding the question fully is rewarded. Students who have a general idea but miss small details like specific words, underlying assumptions, or context clues might be surprised when they get it wrong.

Case-based questions

These questions are meant to see how well you can apply your knowledge when things aren’t perfectly clear. The “right” answer isn’t always about being technically perfect; it’s more about thinking things through logically and reasonably. Students who just try to plug information into memorized formulas might feel lost when the situation doesn’t match the exact template they learned.

Interviews or personality assessments

Here, preparedness is psychological rather than informational. Examiners assess coherence between thought, expression, and judgment. Over-rehearsed answers often feel safe to students but appear shallow to evaluators.

Across formats, the concept being tested is consistent: clarity of thinking under constraint. The form changes, but the expectation does not.

Where most students go wrong

Most mistakes in this area are not errors of ignorance. They are errors of interpretation.

Mistake 1: Equating coverage with readiness

Students feel prepared when they have “finished” material. Exams, however, reward how selectively that material is used.

Mistake 2: Answering the topic, not the question

When a question touches a familiar area, students default to everything they know about it. Examiners notice when the response drifts from the specific demand.

Mistake 3: Treating structure as decoration

Many students see structure as formatting rather than thinking. Lists and headings without prioritisation do not convey clarity.

Mistake 4: Confusing balance with neutrality

In analytical questions, students often present all sides equally to appear fair. Examiners, however, expect judgment—reasoned, qualified, but present.

These mistakes happen because preparation environments rarely train students to decide. They train them to accumulate. Under exam pressure, decision-making feels risky, so students retreat to safety in volume.

How toppers approach this differently

High-performing candidates are not necessarily more informed. Their advantage lies elsewhere.

Thinking style:

They read questions as problems to be solved, not topics to be displayed. Their first instinct is to interpret demand, not recall content.

Answer framing:

They make their central argument visible early. Supporting points are clearly subordinate, not competing.

Prioritisation:

They’re perfectly okay with omitting information that’s relevant but not absolutely necessary. This careful selection actually makes their answers sound more assured. Crucially, this isn’t about being flashy or bold; it’s all about being aligned with what the examiner is looking for. Their responses feel complete because they hit the mark in terms of the examiner’s expectations, rather than trying to cover every single detail.

A practical framework students can reuse

To bridge the gap between preparation and performance, students need a repeatable thinking model. One such framework can be remembered as D–S–P–E.

D: Demand

What exactly is being asked? Identify the action word and the scope.

S: Selection

From everything you know, which points directly serve this demand?

P: Priority

Which of these points matter most? Arrange them accordingly.

E: Expression

Just taking thirty seconds to think about what you’re about to write can really cut down on those feelings of being underprepared. It helps shift your mindset from “What do I actually know?” to “What does this situation actually need from me?” This approach is effective no matter the topic because it lines up with how the person grading your work is likely thinking. It’s less about specific knowledge and more about making the right decisions.

How this way of thinking helps beyond exams

This way of thinking has advantages that go way beyond just passing tests. Developing clear thinking helps with:

- Making smart decisions when things get complicated.

- Writing effectively even when you don’t have much time or space.

- Explaining your ideas clearly without overwhelming people.

In both work and school, being able to do these things is highly valued. It’s about giving exactly what’s needed, not trying to do everything possible. Learning this early on means you rely less on others telling you if you’re good enough and gain more confidence in your own understanding.

Interestingly, many students notice that when they stop trying to make everything perfect, their confidence actually becomes more steady. It’s not necessarily because they know more facts, but because they finally understand what “good enough” really looks like.

Final takeaway

Sometimes feeling unprepared doesn’t mean you’re not good enough. For many smart students, it actually signals that their minds have grown beyond the usual ways they study.

Today’s exams often test your judgment, how well you align your ideas, and your clarity when you’re under pressure and time constraints. If your preparation is just about memorizing facts, this difference can make you feel uneasy.

Learning the real way questions are asked and why they’re asked that way won’t erase your doubts. But it does change how you see them. Instead of constantly wondering, “Have I studied enough?”, you start asking yourself, “Am I really answering what they’re looking for?”

Making that switch in your thinking can often bring a sense of calm that no amount of extra revision ever could.

FAQs

Is this approach useful across different competitive exams?

Yes. While content varies, examiner logic around clarity, relevance, and prioritisation remains consistent across formats.

Can this help students who feel stuck despite regular study?

Often, yes. The issue is usually not effort but alignment between preparation and evaluation.

Why do answers that feel correct sometimes score poorly?

Because correctness alone is not enough. Examiners also assess relevance, structure, and judgment.

How long does it take to see improvement using this way of thinking?

Many students notice changes within a few practice attempts, as the shift is cognitive rather than procedural.

Can beginners apply this approach?

Absolutely. In fact, learning to think this way early can prevent confusion later.

For more analytical exam-focused writing, readers can explore related pieces in the daily series at The Vue Times.