Why this topic matters in today’s exams

You know, there’s a pattern I’ve noticed popping up again and again in competitive exams these days. It’s kind of quiet, but it’s definitely there. Students finish their tests feeling like they absolutely nailed it, certain they knew the answers. But then the scores come back, and… well, they don’t quite match that confidence. This disconnect isn’t exactly new, but it feels like it’s gotten wider lately. I think it’s because exams are shifting away from just testing whether you can remember facts, and moving more towards seeing how you make judgments.

Think about how much information we’re all swimming in these days. It’s everywhere – reports, opinions, stats, explanations… just constant. Exams are starting to reflect that. They’re no longer really about rewarding you for simply repeating information that’s easily found. Now, they’re more interested in seeing how you can actually process information, figure out what’s important, and use it effectively, even when you’re under pressure.

This change in exam style is why one particular error has become so damaging. And honestly, it’s an error almost everyone makes when answering questions: they treat showing off their knowledge as if it’s the same thing as actually answering the question. Back when exams were simpler, that strategy often worked just fine. But these days, it’s quietly leading people down the wrong path.

Students really struggle with this, but it’s usually not because they haven’t prepared at all. The problem is that the way they prepare often reinforces the wrong kind of habit. You know, reading tons, making detailed notes, and drilling the content – all that trains your brain to gather up as much material as possible. But the exam? It wants something different. It wants you to be smart about *using* that material, specifically to address the particular decision or argument the examiner is asking you to consider.

This clash between how students prepare and how they’re actually being evaluated is why this issue keeps cropping up, even for students who are really serious and put in tons of disciplined effort.

How examiners actually think about this area

Examiners don’t start by asking, “How much does this student know?” Their first thought is more straightforward and stricter: “Did the student actually answer the question asked?” Every question is set up around a key decision point. The examiner is trying to see if the candidate can:

- Figure out what the question is really getting at.

- Decide what information is important and what isn’t.

- Use good judgment within the time and context given.

From the examiner’s point of view, an answer isn’t just a box to be filled with facts. It’s evidence of how the student is thinking. The information itself is only useful if it backs up that thinking process.

That’s why questions are often deliberately a bit vague. It’s not to trip students up, but to force them to prioritize. Two students might know the exact same facts. The one who gets a better score is usually the one who realized which facts were most relevant to that specific question.

This is why examiners often aren’t impressed by answers that are factually correct but completely miss the point. Such answers suggest the student didn’t really think about what was needed. They hint that the student is just reciting information instead of actually responding to the question.

Understanding this mindset changes how you should approach reading questions. The examiner isn’t asking for everything you’ve ever learned. They’re inviting a specific line of reasoning and checking how well you can follow it.

How the same concept appears across different papers

The mistake almost everyone makes while answering shows up in different disguises across exam formats.

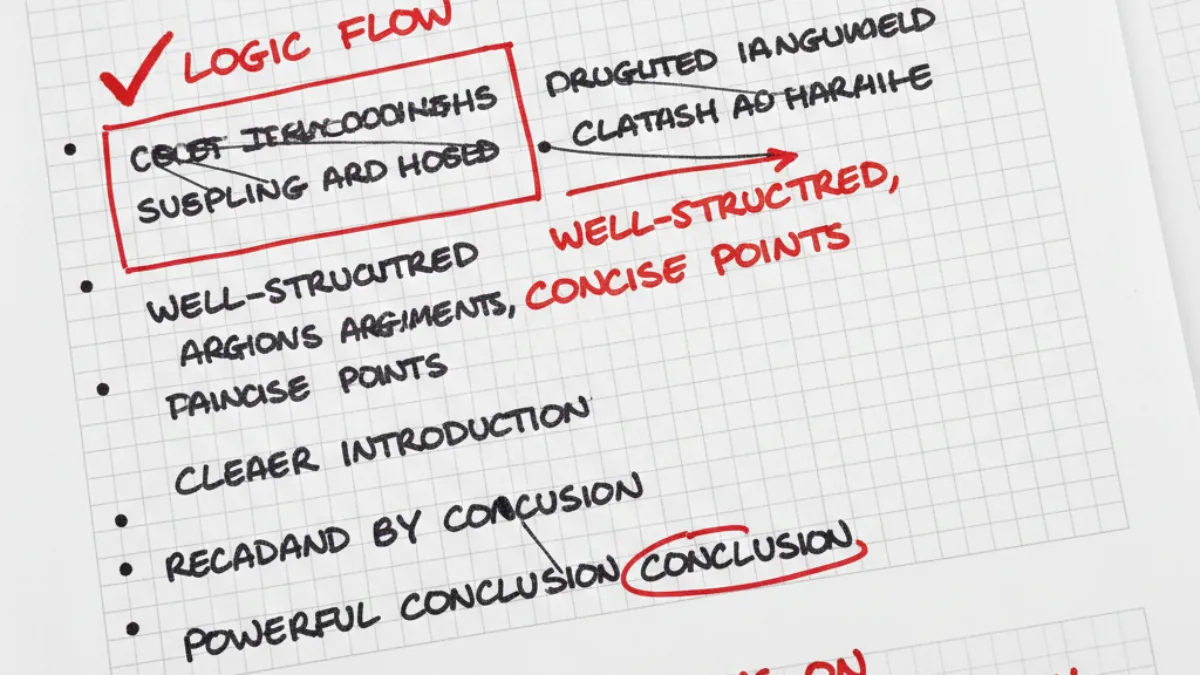

Essay-style questions

Students often make the mistake of thinking longer answers are always better, and they tend to include a lot of extra information. They might give background details, talk about history, define terms, or even bring in multiple viewpoints, but they end up delaying or weakening their actual answer to the question itself.

Examiners easily spot when an answer just goes around the topic without really addressing it. Simply being long doesn’t make up for lacking a clear direction. In fact, an essay is judged more on whether it stays focused on the right points rather than how many points it tries to cover.

Objective or short-answer formats

Here, the same error shows up when students overthink things or misinterpret the question’s intent. They pick choices that are factually accurate but don’t quite fit the context. The person grading wants accuracy. Every option is designed to see if the student can tell the difference between something that’s “generally correct” and something that’s “correct in this specific situation.”

Case-based questions

Case questions are set up to trip up students who give generic answers. Often, students just repeat information from the case or use standard methods without much thought. But the examiner is really looking for something more focused. They want to see which specific detail the student thinks is most important and how that insight influences their whole response.

Interviews or personality assessments

When people talk, this mistake often looks like a case of “information dumping.” Candidates respond to questions by reciting stories they’ve practiced beforehand, rather than tackling the specific issue the question is actually asking about. Interviewers are looking for how clearly a person thinks, not whether they can give a complete life story. The same idea holds true: it’s always better to focus on what’s relevant rather than just saying a lot.

Where most students go wrong

This mistake does not arise from carelessness. It emerges from predictable misunderstanding patterns.

- Treating questions as topics

Students tend to take a question and match it up with a big topic they spent time studying. Consequently, their answer turns into a mini-lecture instead of actually responding to the question. This often happens because, during prep, they focus on learning broad topics, whereas exams actually test their ability to make specific judgments within those topics.

- Confusing correctness with completeness

A lot of people think that if everything they write is factually correct, they’ll automatically get a high score. But here’s the catch: examiners actually mark down answers that include irrelevant details, even if those details are accurate. The problem isn’t about having wrong information; it’s about including information that isn’t necessary.

- Ignoring the command of the question

Often, students treat words like “examine,” “assess,” “discuss,” or “evaluate” as if they mean the same thing. They tend to answer questions based on what they feel most comfortable doing, rather than actually following the specific instructions given.

However, the examiner carefully chooses these terms to signal the kind of thinking and response they’re looking for. Ignoring these subtle differences in the command words weakens the connection between what the student provides and what the examiner expects.

- Writing to display effort instead of judgment

Under pressure, students write to show that they tried hard. Unfortunately, effort is invisible to the evaluator. Only choices are visible: what was included, what was excluded, and why.

How toppers approach this differently

High-scoring candidates do not necessarily know more. They think differently during the answer-writing moment.

Thinking style

They approach every question as something to figure out, rather than just something to fill with words. Their first move is always to figure out what’s really being asked, not to pull facts from memory.

Answer framing

They’re quite okay with leaving some details out, and that’s a really important distinction.

Prioritisation

They believe that focusing on what’s truly relevant is more valuable than trying to cover everything. This way of doing things results in answers that come across as well-thought-out and steady, even when they’re working against the clock.A practical framework students can reuse

The following thinking model can be applied across subjects and formats.

- Identify the decision being tested

Ask: What judgment is the examiner asking me to demonstrate?

- Select, don’t recall

Choose information that directly supports that judgment. Ignore the rest.

- Answer before you explain

State your response early. Use explanation to justify, not to discover, your answer.

- Check alignment

Before moving on, ask: If someone read only my first few lines, would they know I answered the question?

- Stop when the question is satisfied

Do not continue writing just because time remains.

This framework is deliberately simple. Its strength lies in repeatability under pressure.

How this way of thinking helps beyond exams

This way of doing things helps create good habits that last even after the exams are over. It hones clear thinking by making you figure out what’s most important. It boosts decision-making by teaching you to spot what matters and ignore what doesn’t. Plus, it makes you a better communicator by training you to give direct answers instead of just going on and on.

In workplaces and schools, these abilities are quietly appreciated. People tend to trust those who actually answer the question they were asked more than those who just ramble on endlessly. So, in a way, the exam isn’t some fake exercise. It’s like a condensed version of real-life situations where you have to make smart choices under pressure.

Final takeaway

You know what many people get wrong when they’re answering questions? It’s usually not because they don’t know the material. The real issue is confusing simply dumping information with actually giving a proper response.

Once you really get that difference, prepping for exams doesn’t feel quite so overwhelming. The goal shifts from trying to cram in more facts to figuring out how to present what you know more effectively.

This insight won’t magically make you perfect overnight. But it definitely helps cut down on the confusion. And honestly, for a student who’s feeling totally drained, just feeling less confused is often the biggest win of all.

FAQs

- Is this approach useful across different exams?

Yes. Because it focuses on thinking and relevance, not subject-specific content, it adapts well across formats and disciplines. - Can this help students who feel stuck despite regular study?

Often, yes. Many students plateau not due to lack of effort, but due to misalignment between how they study and how they are evaluated. - Why do correct answers still score poorly sometimes?

Because correctness without relevance does not demonstrate judgment. Exams reward decision-making, not data storage. - How long does it take to see improvement using this approach?

Some students notice changes within a few answer-writing sessions. Deeper consistency develops with conscious repetition. - Can beginners apply this way of thinking?

Absolutely. In fact, beginners often adapt faster because they have fewer rigid habits to unlearn.

For more analytical exam perspectives, readers may explore related explainers on The Vue Times.