In a landmark move for public health and consumer protection, the FSSAI has issued a directive banning the use of the term “ORS” (Oral Rehydration Solution) on any food or beverage product unless it strictly follows the medically recommended formulation—essentially outlawing the use of the “ORS” label on sugary drinks or ready-to-drink beverages that do not meet the standard. This decision comes after approximately eight years of persistent advocacy and legal battle led by Hyderabad-based paediatrician Dr. Sivaranjani Santosh.

The ban is significant because “ORS” is not a mere marketing term—it represents a proven, life-saving intervention for dehydration, especially in children with diarrhoea. When misleading products pose as ORS but actually deviate substantially (especially in sugar content, electrolyte balance), they can exacerbate harm rather than prevent it. Dr Sivaranjani’s campaign exposed how some companies were labelling sugary drinks as ORS or using “ORS” in branding, which created a false impression among parents, health-care providers and pharmacists.

This article will outline: the nature of the problem, how Dr Sivaranjani’s campaign evolved, the regulatory journey of FSSAI’s action, the implications (health, regulatory, industry) and the road ahead.

The Problem Misleading “ORS” labelled drinks

What is true ORS?

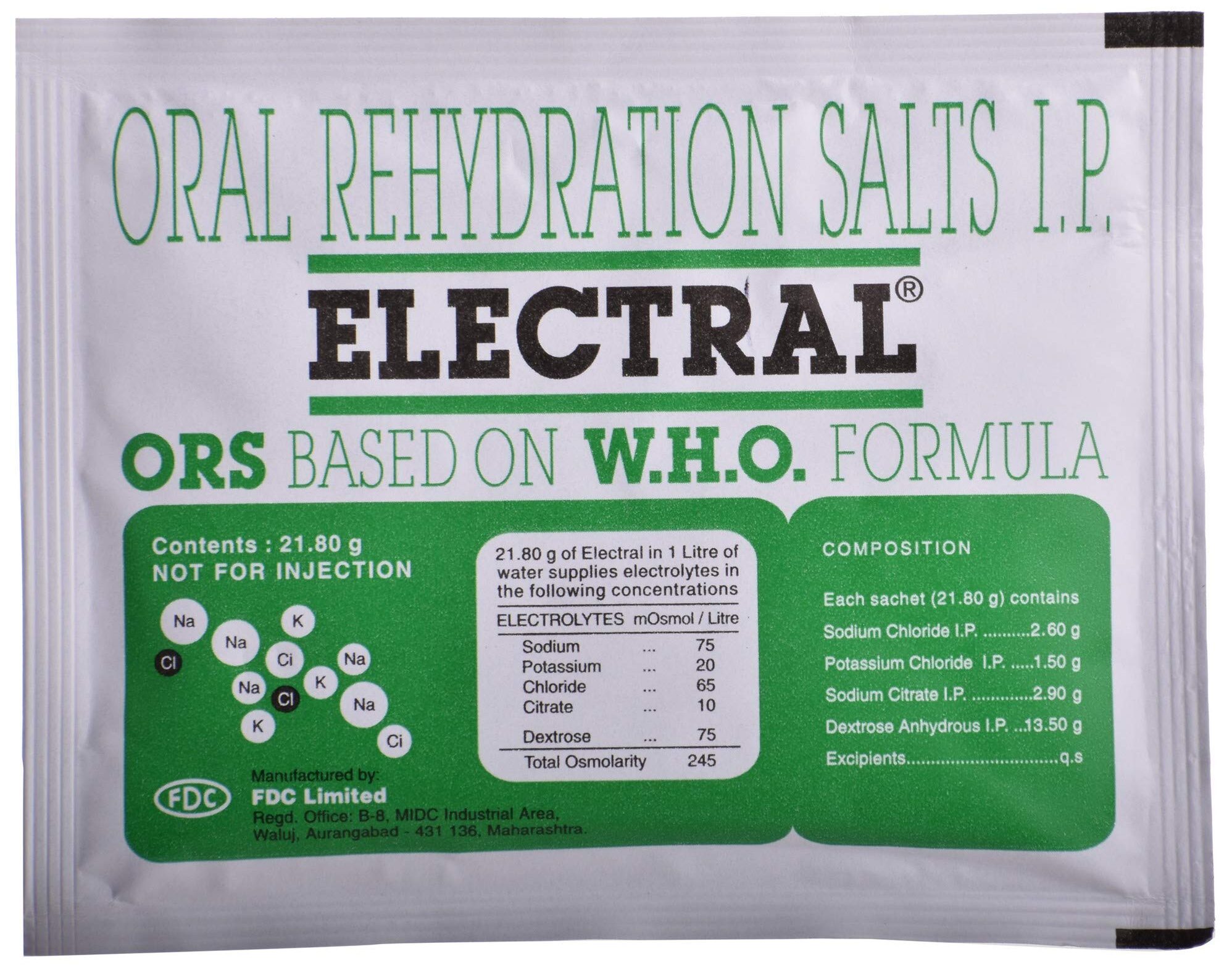

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines ORS (oral rehydration solution) as a simple, precise formulation of glucose (or dextrose) and salts (sodium chloride, potassium chloride, etc) in clean water, designed to rehydrate the body and correct electrolyte imbalance in dehydration (e.g., from diarrhoea or vomiting). The correct ratio matters: too much sugar or wrong salts can distort the osmolarity and lead to adverse outcomes.

For example, a typical WHO-recommended ORS formula has about 13.5 g glucose per litre (i.e., 1.35 g per 100 ml) alongside defined amounts of sodium chloride, potassium chloride, etc.

What went wrong: Sugary drinks posing as ‘ORS’

In recent years in India, multiple beverage-brands marketed tetra-packs or ready-to-drink “rehydration” or “electrolyte” drinks labelled with names like “ORS”, “ORSL”, “Active ORS”, “Rebalance ORS” or similar. These drinks often had much higher sugar content than medically advised, and did not meet the electrolyte/salt composition required of true ORS.

Dr Sivaranjani and other health-professionals documented cases in her paediatric clinic where children treated for diarrhoea and dehydration had consumed these drinks (thinking they were ORS) but fared worse. She pointed out:

“Many commercial drinks contained 8 to 12 grams of sugar per 100 ml — roughly three to five teaspoons per tetra pack — while the correct ORS has only about 1.35 g per 100 ml.”

In effect, these high-sugar drinks can worsen dehydration: excess sugar can draw water into the gut lumen rather than bloodstream, interfering with absorption, and the electrolyte imbalance may persist or worsen

Why children were particularly at risk

In India, diarrhoea remains a leading cause of death in under-five children (around 13 out of every 100 child deaths in that age group, per Dr Sivaranjani’s estimates). When parents, believing a brightly labelled “ORS drink” was safe, administered it instead of genuine ORS sachets or solutions, the risk of harm increased. Moreover, the products were widely available in pharmacies, hospitals, schools and supermarkets, sometimes endorsed by celebrities or placed alongside legitimate ORS. The cumulative result: a dangerous gap between consumer perception and scientific reality.

Industry and regulatory loopholes

The problem was partly enabled by marketing, partly by regulatory ambiguity. Some drinks used disclaimers (“This product is not an ORS formula as recommended by WHO”) but the prominent brand label “ORS” or “ORSL” still created confusion and trust. Some regulatory orders were issued but then relaxed, enabling continued use of “ORS” with disclaimers.

Dr Sivaranjani described how the industry introduced drinks labelled “ORSL”, “IND-ORS” etc, some even without disclaimers, and the regulatory framework initially failed to stop them effectively.

The Campaign Dr Sivaranjani’s Eight-Year Fight

Beginnings and motivations

Dr Sivaranjani Santosh, a paediatrician based in Hyderabad, began noticing in her clinical practice certain children whose dehydration seemed to worsen after being given so-called “ORS” drinks (non-sachet, ready-to-drink). On examining labels, she found high sugar content, improper salt balance. Her medical concern turned into advocacy.

Advocacy, documentation and escalation

Over the following years (from around 2017-18 onward), Dr Sivaranjani:

-

Began alerting parents through social media, Instagram, clinical talks, about the difference between genuine ORS sachets and these “fake” drinks.

-

Wrote to regulatory bodies: initially to the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO), which referred her to FSSAI. She then reached out to the Health Ministry and FSSAI.

-

Collated evidence: labels, sugar content, clinical cases of diarrhoea treatment complications; reported how children and patients with diabetes or vulnerabilities were at extra risk.

-

Filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Telangana High Court in September 2024, naming FSSAI, the Health Ministry and several beverage companies as respondents.

Challenges and setbacks

Dr Sivaranjani faced resistance:

-

Regulatory inertia and reversal of previous orders: In April 2022, FSSAI issued a restriction on use of “ORS” label; by July 2022, they reversed to allow use with a disclaimer. She argued the disclaimer wasn’t enough.

-

Industry lobbying: Some brands exploited the loopholes, launched new drinks using “ORS” in the brand despite inadequate composition.

-

Professional isolation: She has spoken publicly about feeling unsupported by some parts of the medical establishment or facing pushback from commercial interests.

The turning point

In October 2025, on October 14/15, FSSAI issued a sweeping directive clarifying that no food or beverage product shall use the term “ORS” (whether alone, as prefix/suffix or part of trademark) unless it meets the WHO recommended formulation. The order marked the culmination of the eight-year fight.

Dr Sivaranjani described the victory as not just her own, but a win for parents, children and public health. She emphasised that no high-sugar drink can now carry “ORS” on its label.

The Regulatory Response FSSAI’s Directive

What the directive says

The FSSAI’s October 2025 directive (communication to states/UTs and central licensing authorities) states:

-

Any product that uses “ORS” (or any prefix/suffix/part of trademark) in the name of a food product must conform to the WHO-recommended ORS formulation. If it does not, then the term “ORS” cannot be used.

-

The order clarifies that the usage of “ORS” in any form on beverages, fruit-based drinks, non-carbonated/ready-to-drink products is a violation of the Food Safety & Standards (Labelling and Display) Regulations, 2020, and the Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006.

-

Previous orders (July 14, 2022 and Feb 2, 2024) which allowed “ORS” usage with a disclaimer are withdrawn with immediate effect.

-

The directive effectively mandates removal of “ORS” from the labels of all products that do not comply, and makes future usage contingent on proper formulation and approval.

Why this matters

-

It sends a clear regulatory signal that medically associated terms (like ORS) cannot be commodified without meeting strict criteria.

-

It closes a loophole that allowed companies to mislead consumers (especially vulnerable populations) by using trusted medical terminology.

-

It elevates the standards of labeling and advertising compliance in the food-beverage sector, especially when claims overlap with health/medical benefits.

-

It empowers enforcement agencies, health professionals and consumers to call out misuse and demand accountability.

Enforcement and implementation challenges

-

While the directive has been issued, implementation at the ground level will require audits, product testing, compliance checks, removal of non-compliant products from shelves, and possibly penalties for violations.

-

Some companies have already sought stay orders or transitional arrangements to dispose of existing stock (e.g., a mention of a stay requested by JNTL, a subsidiary of Kenvue). Dr Sivaranjani flagged this on social media.

-

Consumer awareness remains critical: even if labels change, parents, pharmacists and caregivers must understand what genuine ORS is and how to use it correctly. Dr Sivaranjani emphasises this.

Impact Health, Consumer & Industry Implications

Health and consumer protections

-

For children with diarrhoea, correct ORS use remains a key intervention in preventing dehydration and mortality. This regulatory shift helps ensure that genuine ORS solutions are distinguishable and not confused with sugary drinks that may worsen outcomes.

-

It reduces the risk of consumption of inappropriate “rehydration” beverages by people (including children, patients with diabetes) under the false belief they are safe ORS. The high sugar content in these drinks posed risks: worsening dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, increased sugar load — not appropriate in pediatric or diabetic populations.

-

For consumers at large, it strengthens labeling integrity: when a health-related term appears on packaging, it better reflects true properties, not mere marketing.

Industry and regulatory repercussions

-

Beverage manufacturers who used “ORS” or similar branding will need to either reformulate their product to meet WHO/medical-grade standards or remove the term altogether. This may involve costs of reformulation, relabeling, marketing repositioning, and compliance approvals.

-

There may be legal/penalty risks if companies continue using “ORS” in violation of the directive. Enforcement actions may be taken under the Food Safety & Standards Act, 2006.

-

The case sets a precedent for other health-related claims in the food-beverage sector: regulators may be more vigilant about medical/health terminology, endorsements, misleading claims and disclaimers.

-

The battle also highlights how regulatory action may be delayed, but persistent advocacy (by health professionals, civil society) can bring change. Industry may need to factor regulatory activism and consumer awareness into their strategy.

Broader public health consequences

-

The directive may contribute, incrementally, to larger public health goals: reducing child mortality from diarrhoea, lowering unnecessary sugar intake, improving health literacy around dehydration treatment.

-

It underscores the interface between nutrition/food regulation and medical/scientific standards: food regulators must align with WHO or medical guidelines when a product claims medical/health usage.

-

The story emphasises the role of individual professionals (here Dr Sivaranjani) in identifying systemic issues, driving evidence-based change beyond their clinic into policy and regulation.

The Hero’s Journey: Dr Sivaranjani Santosh

Background

Dr Sivaranjani Santosh is a paediatrician practising in Hyderabad. Over eight-plus years she observed children coming to her with dehydration or diarrhoea complications — not improving despite being given “rehydration drinks” labelled as ORS. Delving deeper, she discovered a pattern of mis-labelling and marketing of sugar-rich beverages as ORS substitutes.

The campaign

-

She began advocacy: social media (Instagram), parental education, media interviews.

-

She wrote to regulatory bodies (CDSCO, FSSAI, Health Ministry).She documented label content, sugar/glucose analysis, clinical cases showing harm (or lack of improvement) from these drinks.

-

She allied with professional bodies (e.g., Endocrine Society of India) and filed PILs in the Telangana High Court to compel action.

Obstacles faced

-

Regulatory reversals: initial directive April 2022 followed by relaxation in July 2022; companies continued to exploit loopholes.

-

Industry push-back: companies launched new products, used branding variations.

-

Professional isolation: sometimes facing lack of support, industry sponsorships influencing other bodies.

The victory

Finally, in October 2025, FSSAI’s directive came through. The campaign succeeded. Dr Sivaranjani called it a victory for parents and children, emphasised the need for vigilance going forward.

Significance

Her story is emblematic of how one physician’s persistence can trigger policy change. It also shows the interplay between clinical observation, public health advocacy, regulatory action and consumer safety.

Why This Matters: Key Take-aways

-

Medical vs. marketing labels: Terms like “ORS” carry clinical meaning. When misused in product branding, they mislead vulnerable consumers.

-

Sugar paradox: In dehydration, just drinking sweet drinks may worsen the situation if electrolyte and osmolar balance is wrong. High sugar drinks labelled as ORS can therefore be harmful.

-

Regulatory integrity: FSSAI’s role in enforcing accurate labeling and preventing misleading claims is critical. The directive strengthens consumer protections.

-

Importance of awareness: Consumers must know what true ORS is, how to use it (mixing, dosage), and be wary of products claiming “rehydration”, “instant ORS”, “ready-to-drink ORS” unless verified.

-

Industry responsibility: Beverage/drink manufacturers must ensure their products’ claims are accurate, not exploit medical terminology without meeting standards.

-

Role of civil advocacy: This case demonstrates that clinicians, parents, health professionals can effect regulatory change—even against strong commercial interests—if evidence and persistence align.

What Now Implementation and Next Steps

For regulators (FSSAI, State/UT authorities)

-

Ensure the directive is enforced: monitor food business operators (FBOs), check product labels, remove non-compliant items, impose penalties where required.

-

Audit and test formulations to verify compliance with WHO ORS standards.

-

Issue public alerts and consumer guidance about genuine ORS products vs misleading alternatives.

-

Coordinate with health ministries, child services, pharmacy councils to ensure only proper ORS is stocked in hospitals, clinics, schools.

For health-care professionals and paediatricians

-

Educate parents about genuine ORS sachets: how to identify, how to mix, when to use, what not to buy.

-

Raise awareness in clinics, hospitals, especially in rural and lower-income settings where marketing may be more influential.

-

Report suspect products to authorities or consumer groups.

For parents and caregivers

-

Understand that not every “hydration” labelled drink is ORS. Only use WHO-approved ORS sachets when medically indicated (e.g., in diarrhoea).

-

Read labels: check sugar content, salt content, dosage instructions.

-

Avoid replacing medical ORS with sugary drinks, especially for children, diabetics or the elderly.

-

Ask pharmacists for genuine ORS sachets; be wary of colorful tetra-packs labelled “ORS” or “instant ORS” without clear composition.

For the beverage industry

-

Review product branding, names, labelling to ensure compliance with the directive and avoid terms like “ORS” unless your product truly conforms to the formula.

-

If marketing “rehydration”, “electrolyte” or “sports” drinks, ensure labeling doesn’t mislead about therapeutic benefits or substitute for ORS.

-

Consider reformulating or repositioning products away from the “ORS” claim if they aren’t meeting medical standards.

For consumer organisations & media

-

Monitor market shelves for non-compliant products.

-

Publish comparative information about ORS vs “rehydration drinks”.

-

Amplify public health messaging about correct dehydration management.

-

Encourage reporting and transparency.

Reflection Why It Took Eight Years

While the regulatory outcome is positive, the fact that it took approximately eight years to achieve suggests deeper structural challenges:

-

Regulatory inertia: Multi-stage procedures, industry pushback, legal stays delayed swift action.

-

Marketing power: Beverage-companies have strong commercial incentives to exploit health-related terms and large distribution networks (pharmacies, supermarkets, schools).

-

Public awareness: Many consumers lacked the knowledge to distinguish real ORS from misleading drinks; they trusted the label “ORS”.

-

Intersection of food vs medical regulation: ORS straddles the boundary of medical treatment and food/drink product; this blurred line allowed marketing to cross into dangerous territory.

-

Resource limitations: Enforcement, testing, labelling audits require institutional resources, which may lag behind commercial activity.

-

Civil advocacy burden: Much of the impetus for change came from one dedicated clinician (Dr Sivaranjani) rather than proactive industry self-regulation or top-down reforms.

The eight-year period underscores that important regulatory changes often require sustained effort, evidence, public pressure, and legal action.

Why This Could Be a Template for Other Reforms

The “fake ORS” story offers lessons for other areas of food-beverage regulation:

-

Health-related claims must rest on proper formulation and evidence.

-

Medical or therapeutic sounding labels should trigger higher scrutiny.

-

Labeling regulations must keep pace with marketing innovation (e.g., ready-to-drink, sports/rehydration claims).

-

Civil society/clinician advocacy can bridge the gap between clinical risk detection and regulatory action.

-

Consumer literacy is key: regulation alone isn’t sufficient; people must understand what to look for.

Challenges Ahead and Pending Questions

-

Penalties and compliance: Will the industry face penalties for past sales of misleading labelled drinks? Will companies recall or reformulate affected products?

-

Stock disposal: Some companies sought stay orders to dispose of existing stock (e.g., JNTL). Ensuring those drinks are not sold under new names or diverted remains a challenge

-

Awareness and access: Will parents in rural and lower-income communities receive information about this change and about genuine ORS use?

-

Enforcement across states/UTs: Regulatory capacity varies across India. Ensuring uniform implementation is critical.

-

Monitoring new branding tactics: Will companies shift to “ORS-like” branding (e.g., “Rehydrate+”, “Electrolyte Solution”) to circumvent the ban? Regulators must monitor for evasion.

-

Scope beyond drinks: This case dealt with beverages; but similar misleading claims may exist in powders, sachets, “hydration” blends. The regulatory framework may need expansion and vigilance.

-

Long-term health impact: Will this directive translate into measurable reductions in dehydration-related child morbidity/mortality or inappropriate drink usage? Tracking and evaluation will be important.