Why Deficits Matter More Than Ever

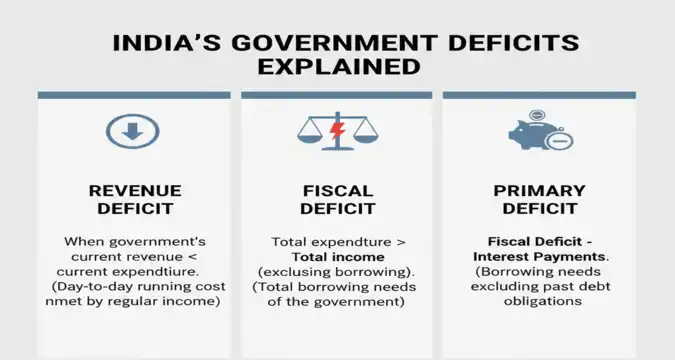

Every year, government budgets make headlines. Numbers are debated, targets are missed, and opposition parties argue over what those figures actually mean. Among the most frequently cited, and least clearly understood, are revenue deficit, fiscal deficit, and primary deficit.

These terms are not just accounting jargon. They reveal how a government earns, spends, borrows, and prioritises. In a time of slowing global growth, rising public expectations, climate spending pressures, and post-pandemic debt hangovers, understanding deficits is no longer optional for informed citizens.

For students, professionals, policy watchers, and decision-makers, these indicators offer a window into economic discipline, political choices, and long-term sustainability. This article takes a deep explainer approach, unpacking each deficit concept carefully, placing them in context, correcting common misconceptions, and explaining why they matter right now.

Read More: How RBI Control Budget

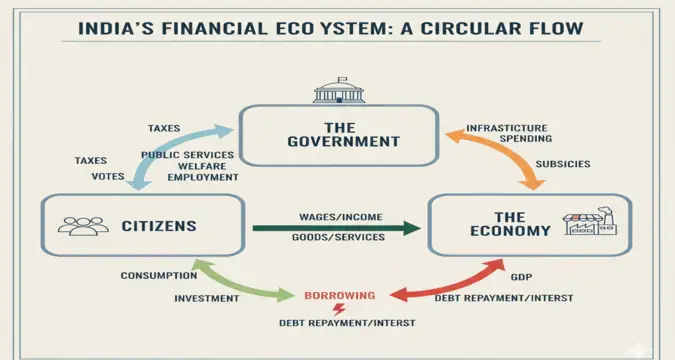

Understanding the Big Picture: How Government Finances Work

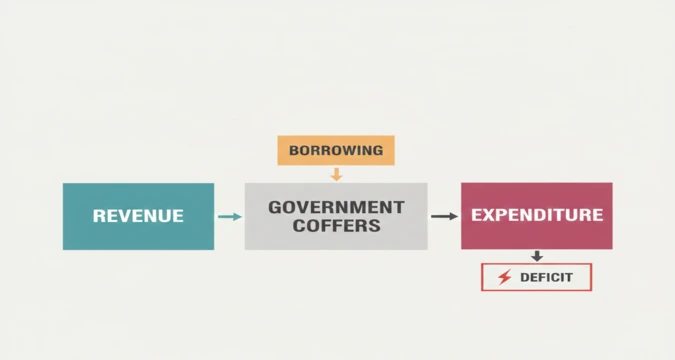

Before diving into individual deficits, it helps to understand the basic structure of a government budget.

At its simplest, a budget has two sides:

Income (Receipts)

Money the government earns through:

- Taxes (income tax, GST, corporate tax)

- Non-tax revenue (dividends from public enterprises, fees, fines)

Expenditure (Spending)

Money the government spends on:

- Salaries, pensions, subsidies

- Infrastructure, defence, education, health

- Interest payments on past loans

When spending exceeds income, the gap is financed through borrowing. Different deficit indicators measure different aspects of this gap.

What Is Revenue Deficit?

The Core Idea in Simple Terms

Revenue deficit arises when the government’s revenue expenditure exceeds its revenue receipts.

In other words, the government is not earning enough through its regular income to meet its routine expenses.

Breaking It Down

Revenue receipts include:

- Tax revenue

- Non-tax revenue

Revenue expenditure includes:

- Salaries and pensions

- Subsidies

- Interest payments

- Day-to-day administrative costs

If:

Revenue Expenditure > Revenue Receipts

→ Revenue deficit exists

Why This Deficit Raises Red Flags

A revenue deficit suggests that:

- Borrowed money is being used for consumption, not creation

- The government is struggling to fund its daily operations

- Future generations may pay for today’s routine expenses

Unlike capital spending, revenue expenditure does not directly create assets or long-term economic capacity.

The Economic Implications of Revenue Deficit

Revenue deficit has deeper consequences than it appears on paper.

Key concerns include:

- Reduced savings for public investment

- Increased dependence on borrowing

- Pressure on interest rates

- Limited fiscal flexibility during crises

In developing economies, persistent revenue deficit often indicates structural issues such as:

- Narrow tax base

- Inefficient subsidies

- Weak revenue administration

Reducing this deficit usually requires politically difficult choices, including subsidy reforms and tax rationalisation.

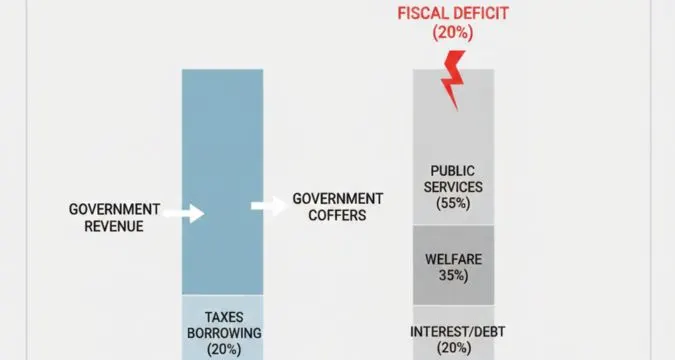

What Is Fiscal Deficit?

The Most Watched Budget Number

Fiscal deficit measures the total borrowing requirement of the government.

It reflects the gap between:

- Total expenditure

and - Total receipts (excluding borrowings)

This indicator captures the overall health of government finances.

How It Is Calculated

Fiscal deficit equals:

- Total expenditure

minus - Total receipts other than borrowings

It includes:

- Revenue deficit

- Capital expenditure

- Interest payments

- Loans and advances

This is why fiscal deficit is often expressed as a percentage of GDP, to show its size relative to the economy.

Why Fiscal Deficit Attracts So Much Attention

Markets, rating agencies, and international institutions closely track fiscal deficit because it signals:

- How much the government needs to borrow

- Potential inflationary pressures

- Impact on interest rates

- Long-term debt sustainability

A rising fiscal deficit can stimulate growth in the short term, especially during downturns. But unchecked, it may:

- Crowd out private investment

- Weaken currency stability

- Reduce policy credibility

This balance between growth support and fiscal discipline lies at the heart of budget debates.

What Is Primary Deficit?

Stripping Away the Past

Primary deficit is fiscal deficit minus interest payments.

It shows whether the government’s current policies are sustainable excluding the burden of past debt.

In simpler terms, it answers:

Is the government borrowing to fund today’s spending, or only to service old loans?

Why This Measure Matters

If primary deficit is:

- Zero → Current revenues cover current spending (excluding interest)

- Negative (primary surplus) → Government is managing its finances well

- High → Structural imbalance in spending and revenue

Primary deficit helps economists isolate the impact of current policy choices, rather than historical debt accumulation.

Comparing the Three Deficits Side by Side

| Aspect | Revenue Deficit | Fiscal Deficit | Primary Deficit |

| Focus | Day-to-day finances | Overall borrowing | Policy sustainability |

| Includes interest payments | Yes | Yes | No |

| Indicates | Consumption vs income gap | Total fiscal stress | Current fiscal discipline |

| Policy signal | Structural weakness | Macroeconomic risk | Reform effectiveness |

Each deficit tells a different story. None should be viewed in isolation.

Historical Context: How These Deficits Evolved

In many emerging economies, including India, deficit patterns have changed over decades.

Key phases include:

- High fiscal expansion during development phases

- Consolidation after balance-of-payments crises

- Counter-cyclical spending during global downturns

- Pandemic-era fiscal loosening

Over time, fiscal rules and responsibility laws were introduced to:

- Limit excessive borrowing

- Improve transparency

- Anchor long-term expectations

Yet, real-world shocks often force governments to relax targets temporarily.

Current Trends: Why Deficits Are Under Scrutiny Again

Several global forces are reshaping fiscal calculations:

1. Post-Pandemic Debt Overhang

Governments borrowed heavily to protect lives and livelihoods. Interest obligations have since risen.

2. Higher Global Interest Rates

Servicing debt has become costlier, increasing pressure on budgets.

3. Climate and Infrastructure Spending

Large public investments are required for energy transitions and resilience.

4. Social Welfare Expectations

Citizens increasingly demand inclusive growth, healthcare, and education.

These pressures make deficit management more complex and politically sensitive.

Who Is Affected by These Deficits?

Deficit outcomes are not abstract. They affect real lives.

Impacts include:

- Taxpayers facing future tax burdens

- Businesses responding to interest rate changes

- Investors assessing policy stability

- States depending on central transfers

- Young citizens inheriting public debt

Understanding deficits helps readers see how budget decisions ripple through the economy.

Common Misconceptions That Need Correction

Misconception 1: All Deficits Are Bad

Not true. Strategic deficits can support growth during downturns.

Misconception 2: Lower Fiscal Deficit Always Means Better Governance

A low deficit achieved by cutting productive spending can harm long-term growth.

Misconception 3: Revenue Deficit and Fiscal Deficit Are the Same

They measure different layers of fiscal stress and require different solutions.

Misconception 4: Borrowing Is Only for Capital Spending

In reality, revenue deficit implies borrowing for routine expenses, which is more concerning.

Nuance matters more than headline numbers.

Linking Deficits to Governance and Accountability

Deficits also reflect governance quality.

- Efficient tax systems reduce revenue gaps

- Transparent budgeting improves credibility

- Outcome-based spending enhances trust

- Strong institutions prevent creative accounting

For readers interested in broader legislative and budgetary processes, related analysis on fiscal accountability can be found on The Vue Times, which regularly examines how policy design shapes economic outcomes.

What to Watch Next: Signals That Matter

Looking ahead, readers should monitor:

- Trends in revenue mobilisation

- Composition of government spending

- Interest payment share in budgets

- Fiscal responsibility framework updates

- Medium-term debt projections

These signals offer better insight than single-year deficit targets.

Key Takeaways for Informed Readers

- Revenue deficit highlights structural weaknesses in everyday finances.

- Fiscal deficit reflects total borrowing and macroeconomic impact.

- Primary deficit shows whether current policies are sustainable.

- No single number defines fiscal health.

- Context, composition, and intent matter as much as size.

Understanding these distinctions empowers readers to move beyond political soundbites.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are deficit numbers debated so intensely every budget season?

Deficits shape borrowing needs, inflation expectations, and growth prospects. They also reflect political priorities. Because budgets influence markets, welfare schemes, and future taxes, deficit targets become focal points for debate across Parliament, media, and financial institutions.

Can a country grow with a high fiscal deficit?

Yes, especially during recessions or emergencies. Growth-supporting spending can justify higher deficits temporarily. The challenge lies in ensuring that such borrowing funds productive investments and that a clear path to stabilisation exists once conditions improve.

Why is the revenue deficit considered more problematic than other deficits?

Revenue deficit indicates borrowing for routine expenses rather than asset creation. This weakens long-term fiscal capacity and limits future flexibility. Persistent revenue gaps often signal deeper structural issues in taxation or expenditure efficiency.

How does primary deficit help policymakers?

Primary deficit isolates current policy impact by excluding interest payments. It helps assess whether today’s spending and revenue choices are sustainable without the burden of past debt, making it a valuable indicator for reform evaluation.

Will deficit management become harder in the future?

Yes. Rising social expectations, climate commitments, and global uncertainty will strain public finances. Balancing growth, welfare, and fiscal discipline will require smarter taxation, targeted spending, and stronger institutions rather than blunt deficit cuts.

Understanding deficits is ultimately about understanding choices, what governments prioritise today, and what they pass on to tomorrow. For readers seeking clarity amid complex economic debates, these distinctions offer a reliable compass.