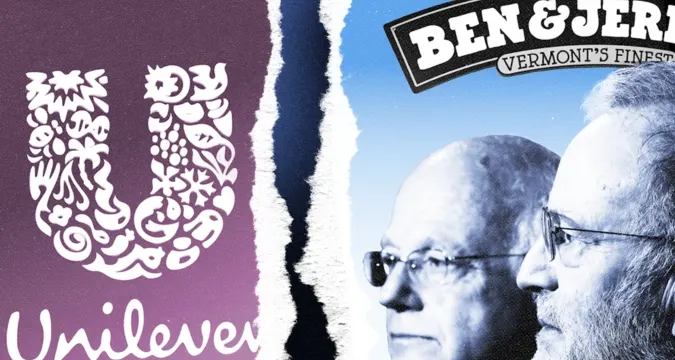

The exit of the founder Jerry Greenfield out of Ben & Jerry out of the company after almost fifty years is not just a case of a founder stepping out of an organization. It is an act that co-solidifies a growing urgency of debate at the nexus of values and value: can an activist-based business continue, unchanged, within the confines of a multinational corporation whose duties to both its shareholders and its regulatory environment tug it in a different direction? Greenfield says no. In his resignation report, the parent company was alleged in the letter to be choking the brand to be able to speak and act out on human rights and social justice matters. To consumers, businesspeople, corporate boards and policy-makers, the episode provides a case study of what may occur when idealism meets scale.

This long-form examination disaggregates the narrative, follows its legal and corporate history, places it in a prophecy of patterns in the wider context of globalized tensions around purpose and profit, compares the Ben and Jerry’s case to other activist brands, and provides actionable advice to founders, investors and regulators interested in steps they can take to remain responsive and still activate their businesses successfully.

The headline and what it means

The departure of Jerry Greenfield was occasioned by what he termed as a progressive tone downing of the autonomous state that Ben and Jerry was assured right after its acquisition in 2000. With that purchase, there was also a unique governance carve-out – an independent board which was meant to ensure that Ben and Jerry retained its mission-focused commitments even as the firm became part of an international group of companies. In the case of Greenfield, this protection has time and again proved to be elusive to block decisions or operational restrictions related by the parent company to dampen the brand activism. His farewell speech was not rhetoric which states retirement. They were an imputation: the brand has been pronounced dumb on the issues which held the founders alive through decades.

At least two factors make the resignation be heard well outside the ice-cream aisle. To start with, Ben and Jerry Company has long been a visible experiment in purpose-driven capitalism, a business strictly intended as a social change vehicle. Second, the process of acquiring and the following governance structure of the company was frequently put forward as an example: how to grow to scale without a sale-out. Once that model will cease to be the case, it prompts a reassessment of the way mission protections are formulated and implemented.

How the conflict evolved: a timeline

The fight that led to the departure of Greenfield did not come out of thin air. It succeeds a series of dramatic episodes cranked up to high tension that revealed structural fault-lines between the still politically activist identity of Ben and Jerry and the realities of international operation of a major parent company.

1978-2000: Founding and growth. Ben & Jerry had built a differentiation of connecting purpose to product attributes – signature flavors, community efforts and vocal advocacy on social matters represented in the brand DNA.

2000: Acquisition with caveats. In the Ben and Jerry takeover of 2000, acquirer Unilever provided advice of governance to maintain the social mission of the company with an independent oversight mechanism. The condition was exceptional and meant to maintain activism as part of the business brand even after being acquired.

2021: The fallout and the West Bank decision. Among the flash tankers was the move of Ben and Jerry with respect to the sales in the West Bank. The relocation had given rise to a high amount of pressure, political scandal and litigation. It is what observers pointed to as a pointer of the boundaries that the big parent might impose on the freedom of action of a provocative brand.

2022-2024: Experts increasing governance tension. Through a set of stand-inside and outside controversies, the founders and the independent watchdog mechanisms held that Unilever had made efforts to remove the activist effect of the firm – through communications and donations and through top management transitions.

2025: Spin-off and exit. Unilever proceeded in selling off its ice cream business to a new listed company The Magnum Ice Cream Company, further raising concerns about how the mission of the brand would be maintained. In the same series of structural actions, Jerry Greenfield resigned, initiating that he could not continue to work with a firm that could not entirely speak.

The legal and contractual heart of the dispute

In the middle of the argumentation is the writing of the acquiring contract and the viable force that it presented. There were clauses stipulated in the 2000 merger accord that were intended to ensure that Ben and Jerry could follow a social mission. Such structural protection had its oddities: in most acquisitions, the financial combination and the control of business operations are the dominant priority, whereas in the case of Ben and Jerry, the negotiated structural protection was an independent system of governance and was aimed at preserving the reference voice of the brand. This fact alone (the presence of the clause) does not necessarily mean unceasing un regulation. Contracts do not always carry the same meaning, business cultures progress, and power in a big business might eventually decide which meaning to follow.

Three legal realities presented below are important now. To begin with, protective language must have active political good will and institutional respect in order to work. Second, spin-offs of segments of a business or ranks of the board can shift the locus of control by a parent company in a manner that pulls down preceding safeguards without technically violating a language that never has been iron-clad. Third, the litigation is expensive, time-intensive and unpredictable, and mission protections are usually enforced by courts or regulators when there is a failure in governance mechanisms.

According to the founders and their advocates, Unilever has done all these (replacing executives, obstructing some pronouncements or obstructing access to transactions that may have resulted in a buyback) and, therefore, these acts have breached the spirit of the original agreement, not necessarily the letter. Unilever is adamant that it has endeavored to collaborate with Ben & Jerry’s and that the structural distance is a business approach to unlock value and expansion. The border between acceptable corporate management and illegal brand principle repression resides within legal regulation and is the area where upcoming struggles will be fought.

Why activist brands matter in the marketplace

This Ben & Jerry was not constructed to make a statement. It was technically used specifically as a means of communications to gather funds, interest and pressure to social causes and at the same time marketing consumer goods. The model that was developed came up with layers of value: loyalty of consumers to like-minded customers, reputational capital to impact a policy and public debate, and employee engagement that came out of a meaningful mission.

The market implication is simple, an authentic activist brand can create loyalty, price strength, as well as earned media. The danger too is simple: activism is provocative, and provocation may entail material extra expense. In the case of corporate parents, the calculation is different. Multinationals have to deal with wide bases of investors, geopolitical risks, multifaceted regulatory settings and fiduciary responsibilities. What it produces is natural tension. That tension is magnified in the case of Ben and Jerry and it is the question of whether the two logics can co-exist over decades or whether one will overwhelm the other.

Comparisons with other activist brands: lessons and contrasts

Glancing at the broader view of the brands which have adopted social purpose reveals a roadmap to mission sustainability and pitfalls to avoid.

Patagonia: control and structure by founders.

The example of Patagonia is frequently mentioned as the brand that has retained a high level of independence and activism. Continuity in leadership, direct ownership by stewards with a mission-oriented approach, clear environmental pledges to corporate governance, and a clientele who appreciate authenticity have enabled Patagonia to be vocal with sustainable commercial business viability. Where Ben & Jerry’s were forced to use carve-outs in the broader corporate takeover, Patagonia structure has traditionally been more biased towards ownership-purpose alignment pulling back the threat of external dilution.

TOMS Shoes: scaling intention without sustainable direction.

TOMS was the company that made its way to the top with a buy-one-give-one model, but during the company’s growth, people began questioning the efficiency and sustainability of the remaining model of philanthropy. Once founders are strong it can take the crowd only a short time to reevaluate the claims of the brand, or when investors prioritize expansion over programmatic rigor. The experience of TOMS highlights the importance of having a mission with open measurement of impact and governance that persists beyond changes of leadership.

Starbucks: activism on a global base in a voluntary manner.

Starbucks often leveraged its position to implement liberal workplace practices and social positions in cultural matters, but it exists under the format that all companies in the sector are publicly traded. Starbucks exhibits an in-between way: larger-scale companies have the freedom to make visible decisions, yet, they are long-disabled by adjusting them to market shareholder demands, legal risk risks as well as global operation needs. The model demonstrated by Starbucks implies that activism can be incorporated into big companies when it is usually selective and can be reversed when the commercial or regulatory interests are transformed.

What these comparisons reveal

- Ownership matters. Energy, mission-focused ownership minimizes the risk of value killing following the scaling or acquisition.

- Governance matters. Carve-outs of the law can assist but not a replacement of continuous institutional investment and enforcements.

- Data regarding transparency and impact are important. The better brands can roll out quantifiable results, the better placed is in asking some fervent stakeholders to switch to brands.

- It does matter that there be cultural integration. Embedded activism on governance, operations and supply chain is less prone to being viewed as discretionary or symbolic.

Ben and Jerry is not like either of these situations since it consumed good activism and a takeover by a company whose main responsibility is to shareholders globally. The 2000 governance accommodation was pioneering, and this episode illustrates how accommodations can tear apart in the absence of mechanisms to ensure the protections last long-term amid corporate changes.

The spin-off factor: The Magnum Ice Cream Company and shifting incentives

The case of the merger and spin off of the ice cream businesses at Unilever, and an ice cream business, The Magnum Ice Cream Company, is a strategic business initiative aimed at streamlining the parent organization and to establish an investable focus ice cream business. In the case of investors, the spin-off can focus the revenue and margin story and extract values. To activists and mission-driven stakeholders, the same move brings in questions, does a new publicly listed ice- cream company make new opportunities of independence or just rebrand the brand under a corporate shell with new governing incentives?

Spin-offs change incentives. They keep turning to management teams and boards whose responsibility is to please a smaller group of the investors, who are concerned with operational performance. That concentration can afford to decontextualize activism when it is viewed to take profit away. On the other hand, the formation of a new listed company would allow mission critical investors to take significant equity, or offer a process to re-bring the company back into hands of the founders or mission entitled investors. This will be determined by the applicant of direction by whoever purchases shares as well as the applicant of director on the new board and the enactment of the independence clauses should they exist in various jurisdictions.

Scenarios ahead: plausible outcomes and their implications

The period of 12 to 36 months will be when Ben and Jerry goes down in history over whether their activism could survive in any form. There are a number of circumstances that are realistic.

- Reader remission by buying back or new ownership.

Assuming that founders or investors aligned with the mission capital-raise Ben and Jerrys to purchase the brand, the company can be reverted to an independent set up, which will reclaim activist independence. It would be the most logical to be able to reconcile purpose and practice although it would demand significant capital and goodwill of negotiation. It is also based on the willingness of Unilever or the spin-off company to sell.

- Semi-independence with formalized precautions.

New legally binding guardrails that persist through changes in the company could be negotiated by stakeholders and include more robust covenants related to the twin executive compensation, the independence of the audit, as well as across-jurisdictional accountability controls. This would be a concession: activism would still persist, but with more definite boundaries and stricter requirements on reporting.

- Further watering down under corporate principles.

When the current trends stayed the same and the stewardship of the ice-cream brand turned out to be less important than the governance choices made by the new parent or its investors, Ben and Jerry may engage in another layer of pretended activism even as its stakes turn formless. The brand would probably potentially remain on commercial sales but may end up losing brand equity over the long term as those core supporters would see hypocrisy against it.

- Interventions by law, regulation.

High profile cases such as this may prompt policymakers to tighten regulation of claims on mission focused policies by making them share information about the governance that claims to uphold social mission or legal classifications of certified mission focused businesses with some measure of enforceable protection. This would leave a legacy of future acquisitions of purpose-led firms.

All the scenarios have various implications on customers, employees, investors and activists. We expect the most resilient ones to be integrated with the legal and governance framework to tie the ownership to mission.

Practical lessons for founders and investors

The resignation of Jerry Greenfield serves as a list to check on by business people and people acquiring them.

- Negotiate structural permanence and not symbolic language. Carve-outs and boards can be helpful, but founders must pursue enforceable arrangements: supermajority rights, veto rights over certain governance activity, or escrowed rights that might become exercisable in case of mission erosion signals.

- Planning according to future corporate changes. Bring spin-offs, re organizations and changes in jurisdiction. Make sure that protection is strong both in legal forms and geography.

- Develop impact measurement and report standards. Activism can be measured and audited, and thus cannot be easily relieved as rhetoric. Integrate transparent KPIs, which are legally binding.

- Develop invested capital. Founders ought to think at the beginning itself on who one would be able to buy their products. Alignment matters. Should sale be a probable exit, build relationships with investors who are also mission parity educational.

- Systematize culture in the operation and not governance. The further a mission is endowed to procurement, hiring, incentives and product development, the more difficult it is to decouple it without operational indigestion being evidenced.

- Make contingency plans on how to advocate to the population. Public movements questioning those in positions of power will attract attention. Are legally, PR, and financial contingent planning so I do not give up when under pressure.

The consumer question: does mission matter at the point of purchase?

It was a sort of consumer protest to many of their customers to make a purchase of a pint of Ben and Jerry’s– a form of protest by consumption. Now the issue of concern is whether consumers will still translate purchase into advocacy when the activism by the brand becomes diluted.

The pattern of research and consumer behavior propose two patterns. There are those consumers who are largely attached to brands which reflect their attitudes and they will fly away when authenticity is lost. Others consider brand purpose as the bonus but they place greater emphasis on product quality, price and convenience. It is the prevailing pattern that will guide the effect of any perceived dilution on the commerce.

What is more crucial, there is a medium category of consumers seeking authenticity but attentive to details and accountability. They require proven action, not utterances. In case Ben and Jerry is felt to be censored, the company would require a credible restoration plan, transparent promises, independent checks, probably new ownership patterns, to hold on to this generation.

What regulators and standard-setters should consider

The Ben and Jerry policy gap is identified in the episode. Consumers and civil society are left with no option but to resort to little under the brands making such commitments to their mission and lacking the instruments to assure them of delivery. Some innovations to add to the regulatory functions that more tightly align include:

- Short private implementation bloc: The provisions of the governance mechanisms that store mission claims in acquisitions are required to be disclosed.

- Legally binding auditable third-party certification frameworks of mission integrity.

- Board of mission company Fiduciary transparency On sale or restructuring, to balance between shareholder value and their declared social responsibility.

Such reforms are not simple, cross shorter than jurisdictions and hopefully designed to avoid making loopholes. But high profile conflicts can be the organizing grounds of constructive policymaking; the task here should be to develop clear expectations and fixes, not to cripple sound commercial dealings.

A founder’s legacy and the work that remains

It is a personal transition, as well as a public indication, that Jerry Greenfield resigned. He has said he wants to carry on the advocacy practice beyond the firm he had contributed in building it. That is one lesson that the power of founders is not limited with the departure of the corporation position – it may be transferred to networks, charity, new media and other initiatives.

To Ben and Jerry the existential question taking place is whether the identity of the brand will be characterized by its past activism or the current restraints. That will decide whether the company continues being a lodestar of purpose-led business or, as with scale, it perverts principles without the strong countervailing design.

Reconciling conscience with commerce

The moral play between Jerry Greenfield and the corporate model which has taken the over control of Ben and Jerry is an example of moral play in these times. It is one of compromise, courage, the short term risk and long term credibility. It also concerns the design of governance and the facts of capital in the world. The main lesson is practical but not moralistic, ideals like founders wish their mission to ensure they have to develop insurances that are legally robust, embedded operationally, financially backed and culturally embedded. Words alone will not suffice.

It is a crossroad in the world of business. Society is growing psychiatrically in its expectation that companies must behave responsibly. Investors are understanding how to value environmental factors, social factors and governance factors. Policymakers are starting to understand that mission claims that lack enforceable promises are subject to cynicism and, in certain instances, even do harm.

Since Jerry Greenfield is quitting his job after 47 years, many will take the experience of Greenfield leaving as a lesson. It is also meant to be read as a call to action: to founders be more precise in their exit planning, to investors to be less hypocritical in the trade-offs of ownership, and to regulators to provision structures that allow sustainable mission-driven firms. When these actors take this lesson to heart, the episode could eventually bring improvement in the form of a new set of practices and institutions that enable brands to be honest to their principles when they are acting on a large scale.