The National Education Policy 2020 constitutes the most comprehensive restructuring of India’s education governance framework in over three decades. Rather than functioning as a narrow curricular revision, it attempts systemic redesign across school architecture, higher education regulation, research financing, digital integration, and centre–state coordination. For competitive examination preparation and advanced policy literacy, the National Education Policy 2020 must be examined as an institutional reform instrument embedded within India’s constitutional structure, fiscal capacity, and administrative capability.

India’s education system operates at a civilizational scale: over 250 million school students and more than 40 million higher education learners. Reforming a system of this magnitude is not a pedagogical exercise alone; it is a governance challenge. The policy seeks to transition education reform India from an access-expansion model toward a quality- and flexibility-oriented institutional framework. Understanding its design requires structured analysis across context, institutional architecture, operational mechanics, fiscal implications, implementation risk, and long-term state capacity impact.

Policy Context

Historical Evolution of Education Reform

India’s earlier comprehensive education framework was the National Policy on Education (1986), modified in 1992. That policy emerged in a period marked by:

- Low literacy levels

- Limited higher education penetration

- Centralised curriculum orientation

- Modest private sector participation

The primary objective was expansion: building schools, increasing enrolment, and broadening access. Post-1991 liberalisation altered the economic structure, increasing demand for skilled labour in technology, finance, and services. By the 2010s, three structural issues became visible:

- Learning Outcome Deficits – Surveys such as ASER consistently showed foundational literacy gaps.

- Regulatory Fragmentation – Multiple higher education regulators operated with overlapping mandates.

- Research Underperformance – India’s research expenditure remained below 1% of GDP, limiting global competitiveness.

According to the All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) 2018–19, the Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) in higher education stood at 26.3%. While expansion occurred, qualitative transformation lagged.

Demographic Imperative

India’s demographic profile intensified reform urgency. A large youth population creates potential economic dividends only if educational quality aligns with labour market demand. Without structural reform, demographic advantage can convert into unemployment pressure.

Governance Imperative

Education moved to the Concurrent List through the 42nd Constitutional Amendment (1976). This created shared legislative authority between Union and States, but coordination mechanisms remained uneven. The National Education Policy 2020 emerged partly as a governance harmonisation attempt within this federal framework.

Institutional Architecture

Administrative Authority

The policy is implemented by the Ministry of Education, renamed in 2020 from the Ministry of Human Resource Development. The renaming signals a conceptual reorientation from manpower planning toward holistic education governance.

The Ministry functions as:

- Policy formulator

- Central coordinating authority

- Funding channel for centrally sponsored schemes

- Regulatory reform initiator

Parliamentary and Legislative Dimensions

The National Education Policy 2020 was approved by the Union Cabinet in July 2020. It is a framework document rather than a statute. Full implementation requires:

- Amendments to the University Grants Commission (UGC) Act

- Legislative creation of the Higher Education Commission of India (HECI)

- State-level legislative and executive alignment

Because education is in the Concurrent List (Article 246), States retain executive authority over implementation. Thus, the policy depends on cooperative federalism rather than unilateral central imposition.

Regulatory Rationalisation

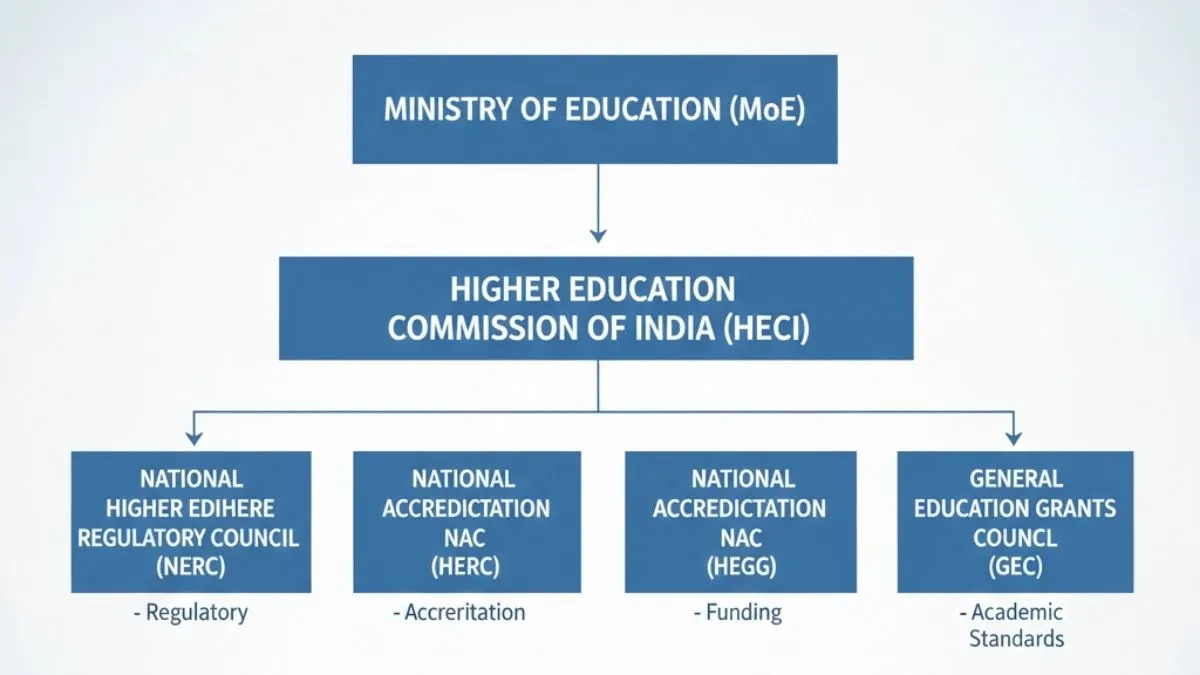

Prior to reform, higher education regulation was divided among UGC, AICTE, NCTE, and NAAC. The proposed HECI structure under the policy introduces four verticals:

|

Vertical |

Function |

| NHERC | Regulation |

| NAC | Accreditation |

| HEGC | Funding |

| GEC | Academic Standards |

This separation aims to reduce conflicts of interest and increase transparency. Previously, bodies such as UGC simultaneously handled funding and regulatory oversight, creating structural overlap.

Financial System Interface

Though not directly implementing education policy, the Reserve Bank of India influences the sector indirectly through:

- Education loan regulations

- Priority sector lending norms

- Liquidity conditions affecting private institutions

Credit accessibility shapes participation in higher education, particularly for middle-income households.

Institutional Reference Suggestion

For authoritative examination preparation, reference to the AISHE reports published by the Ministry of Education is essential. These reports provide official data on enrolment, institutional count, and faculty strength, forming the empirical base for evaluating NEP impact.

Mechanism & Operational Framework

The policy operates through structural redesign across school education, higher education, and research governance.

School Education Reform

Structural Transition: 5+3+3+4 Model

The policy replaces the traditional 10+2 system with a 5+3+3+4 structure:

Stage 1: Foundational (5 Years)

– 3 years Anganwadi/Pre-school

– Grades 1–2

Stage 2: Preparatory (3 Years)

– Grades 3–5

Stage 3: Middle (3 Years)

– Grades 6–8

Stage 4: Secondary (4 Years)

– Grades 9–12

This realigns formal schooling with cognitive development stages, integrating early childhood care into structured education.

Foundational Literacy and Numeracy

A national mission prioritises universal literacy by Grade 3. Structural reasoning is straightforward: early-stage deficits compound over time, lowering overall system productivity.

Assessment Reform

Board examinations are redesigned toward competency-based evaluation, reducing memorisation emphasis. Modular testing allows subject-specific flexibility rather than a single high-stakes exam cycle.

Higher Education Reform

Multidisciplinary Model

Standalone institutions are encouraged to evolve into multidisciplinary universities. The affiliating college system, often characterised by administrative centralisation, is gradually phased out.

Academic Bank of Credits (ABC)

Structural Diagram Explanation:

Student Enrols in Institution A

↓

Completes Courses → Credits Earned

↓

Credits Stored in Academic Bank (Digital Platform)

↓

Transfers to Institution B

↓

Degree Completion Using Aggregated Credits

This introduces academic mobility and reduces drop-out penalties.

Four-Year Undergraduate Programme

Exit flexibility is institutionalised:

- 1 Year – Certificate

- 2 Years – Diploma

- 3 Years – Bachelor’s Degree

- 4 Years – Bachelor’s with Research

This aligns academic duration with labour market realities and research pathways.

Research Ecosystem Reform

The policy proposes the establishment of a National Research Foundation (NRF). Its objectives include:

- Competitive peer-reviewed funding

- Interdisciplinary research encouragement

- Institutional research capacity strengthening

India’s research spending remains below 1% of GDP, underscoring structural limitations.

Economic and Governance Implications

Fiscal Health

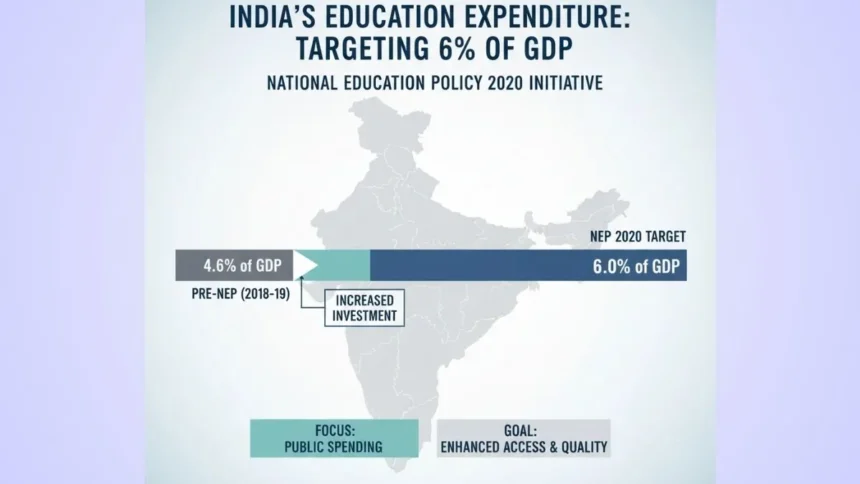

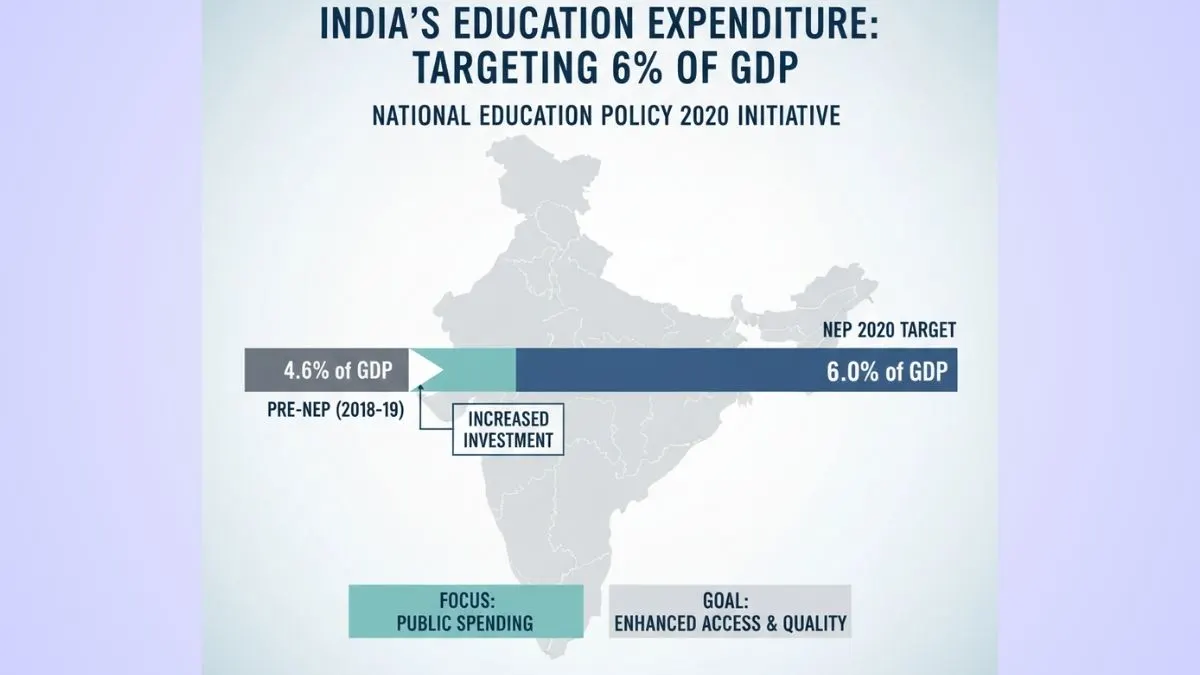

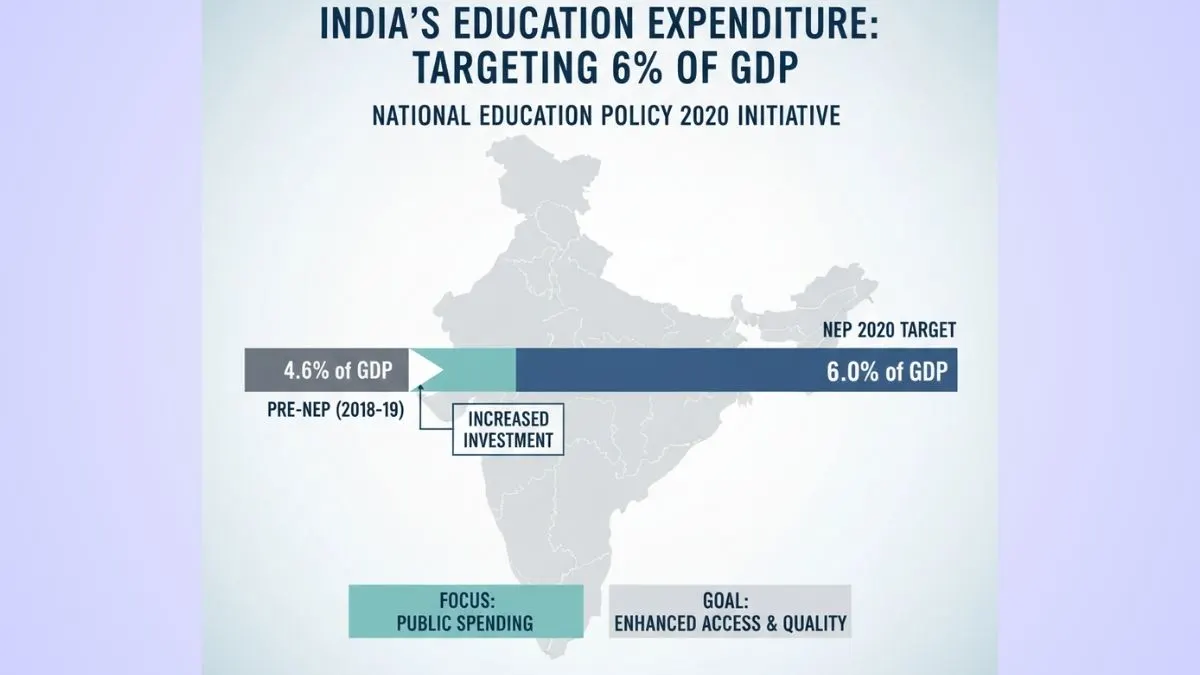

The policy reiterates a long-standing target of allocating 6% of GDP to education. Historically, combined public expenditure has hovered around 3–4%.

Fiscal implications include:

- Infrastructure expansion

- Teacher recruitment and training

- Digital infrastructure development

- Research grants

Without sustained fiscal commitment, reform depth remains constrained.

Federalism

Education reform India depends on Centre–State fiscal coordination. States retain authority over:

- Teacher hiring

- Curriculum contextualisation

- Institutional governance

Thus, NEP impact may vary across states depending on administrative capacity and fiscal health.

Administrative Capacity

Reform execution requires:

- Accreditation transparency systems

- Data governance mechanisms

- Institutional leadership training

- Monitoring and evaluation frameworks

Administrative modernisation becomes central to implementation success.

Private Sector Dynamics

Private institutions account for a significant share of higher education enrollment. The policy’s emphasis on accreditation-based differentiation may lead to:

- Institutional consolidation

- Increased quality competition

- Transparent fee disclosure norms

However, equity concerns persist if financial aid mechanisms are insufficient.

Implementation Gaps

Funding Constraints

The 6% GDP allocation lacks statutory enforcement timelines.

Teacher Shortages

Vacancies and uneven training standards persist across states.

Digital Divide

Technology integration depends on broadband access, which remains uneven in rural regions.

Regulatory Transition Risks

Replacing legacy regulators requires careful sequencing to prevent institutional vacuum.

Institutional Governance Culture

Autonomy demands managerial competence. Many institutions lack experience in financial planning, academic strategy, and research management.

Criticism & Counter-Arguments

Centralisation Concerns

Critics argue national standards may centralise control. However, separation of regulation, funding, and accreditation enhances transparency.

Commercialisation Risk

Autonomy could increase market orientation. Counter-argument: accreditation transparency and disclosure norms can mitigate excesses.

Implementation Overstretch

Simultaneous reforms risk administrative overload. Yet incremental reform historically failed to resolve fragmentation.

Language Policy Debate

Complexity in multilingual implementation remains, though flexibility provisions reduce rigidity.

Balanced assessment indicates outcomes depend more on execution sequencing than conceptual design.

Future Outlook (5–10 Years)

If fiscal allocation and administrative reform align, potential developments include:

- GER expansion toward 50% by 2035

- Reduction of affiliating college dominance

- Strengthened research output through NRF

- Normalised credit portability

- Competitive federalism among states

However, disparities in state capacity may widen regional educational inequality.

The long-term NEP impact will hinge on sustained political commitment across electoral cycles and consistent budgetary prioritisation.

Conclusion

The National Education Policy 2020 represents a structural redesign of India’s education governance architecture. It integrates regulatory rationalisation, curricular flexibility, research financing reform, and digital integration within a unified framework. Its ambition lies in transitioning from enrolment expansion to systemic quality enhancement.

For competitive examination preparation and governance literacy, the National Education Policy 2020 must be analysed through fiscal feasibility, federal coordination, administrative capacity, and regulatory coherence. Education reform India stands at an institutional inflection point. The policy’s long-term success will depend not on textual articulation but on sustained execution discipline, transparent monitoring, and intergovernmental cooperation.

The structural trajectory shaped by the National Education Policy 2020 will determine whether India’s demographic potential translates into sustained human capital competitiveness over the coming decade.