Ladakh, India’s northernmost region, has always occupied a special place in the imagination of the nation. Breathtaking landscapes, resilient communities, and a rich Buddhist heritage define its cultural and geographic uniqueness. Yet in recent years, Ladakh has become more than just a tourist paradise or a strategic frontier. Since its separation from Jammu and Kashmir in August 2019 and elevation to the status of a Union Territory (UT), the region has stood at a historic crossroads. For many Ladakhis, the change brought both hope and apprehension. For the Government of India, it was an important step to provide focused governance, strengthen border security, and accelerate development.

However, as with most transformative policies, the path has not been without friction. Today, Ladakh is witnessing debates on statehood, inclusion under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, job reservation, land rights, and environmental sustainability. These demands are rooted in real anxieties: the fear of losing cultural identity, the risk of outsiders dominating limited resources, and the fragile ecology being overwhelmed by unchecked development. At the same time, the central government emphasizes infrastructure, strategic security, and integration with India’s larger development agenda.

We will explore Ladakh’s history, the issues that matter most to its people, and the deep cultural and environmental stakes at play.

The Historical Background of Ladakh’s Identity

Ladakh’s history has been shaped by its geography. Surrounded by the Karakoram and Himalayan ranges, it has long been a frontier region connecting India, Central Asia, and Tibet. Its people, mostly Buddhists in Leh and Muslims in Kargil, have evolved traditions of resilience in one of the harshest climates on Earth.

For centuries, Ladakh remained relatively isolated, governed by local kings and later integrated into the Dogra kingdom in the 19th century. After independence, it became part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. However, Ladakhis often felt sidelined in the political arrangements of that state, with decision-making heavily concentrated in Srinagar and Jammu. Leaders and citizens repeatedly argued that their voices were not adequately represented.

The 2019 decision to revoke Article 370 and split Jammu and Kashmir into two Union Territories—J&K and Ladakh—was seen as a historic change. Many Ladakhis initially welcomed the move because it promised direct governance from New Delhi and freedom from what they perceived as decades of neglect by the J&K administration. Yet, as months turned into years, concerns about political disenfranchisement, environmental threats, and the absence of constitutional safeguards began to dominate local discourse.

Why Ladakhis Are Demanding Statehood

One of the central demands from citizens and regional groups is full statehood for Ladakh. Currently, as a Union Territory without its own legislative assembly, Ladakh is governed directly by the Lieutenant Governor appointed by the Centre. This arrangement provides administrative efficiency but leaves little room for democratic representation.

Many locals feel this system reduces their say in policy-making. While the Hill Development Councils in Leh and Kargil exist, their powers are limited. Important decisions on land, jobs, and resources are taken by bureaucrats or central ministries, not elected representatives from Ladakh itself.

For Ladakhis, statehood is not just about political power—it is about safeguarding identity, culture, and land. They fear that without a legislature and constitutional guarantees, Ladakh could become vulnerable to outside corporate interests and unchecked tourism-driven exploitation.

The Sixth Schedule Demand

Closely tied to statehood is the call for inclusion of Ladakh under the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution. The Sixth Schedule, currently applicable in parts of the Northeast, provides special rights for tribal communities over land, culture, and governance.

Nearly 95% of Ladakh’s population is tribal, which strengthens the case for such protection. Local leaders argue that Sixth Schedule status would legally safeguard land ownership against outsiders, protect natural resources, and empower autonomous councils to manage local affairs.

For instance, without such protection, there is concern that large companies could buy vast tracts of land for mining, industries, or tourism resorts. Given the limited arable land in Ladakh, this would directly threaten the survival of villages dependent on subsistence agriculture and grazing.

Environmental Fragility: Development vs. Ecology

Ladakh’s environment is both its pride and its vulnerability. With high-altitude deserts, rare wildlife, and glaciers feeding major rivers, the region plays a crucial role in India’s ecological balance.

Yet, the ecology here is extremely fragile. A small rise in temperature or a spike in vehicular traffic can disturb its natural systems. Climate change has already caused glacier retreat, reduced snowfall, and water scarcity in many areas. Traditional farming patterns are being disrupted, and villages face uncertainty about drinking water supplies.

Local activists fear that large-scale infrastructure projects—highways, hydroelectric dams, and military installations—could worsen this fragile balance. While such projects are important for connectivity and security, they risk irreversible ecological damage if not planned with sensitivity.

Cultural Identity and the Fear of Dilution

Ladakhis take great pride in their cultural identity, shaped by centuries of Buddhist monasteries, folk traditions, and communal harmony. Yet, with increasing tourism and outside migration, many feel their way of life is under threat.

In Leh, for example, traditional homes are rapidly being converted into guesthouses. Local crafts face competition from mass-produced items. The younger generation, while eager for opportunities, also worries about losing touch with its roots.

The demand for constitutional safeguards is, therefore, also a demand to protect Ladakh’s cultural fabric. Unlike many other regions, Ladakh’s population is small—about 3 lakh people. Without legal protection, they fear being outnumbered or economically sidelined if large-scale migration takes place.

Jobs and Employment Concerns

Employment remains a major issue. Government jobs, especially in defense-related services, have long been the backbone of Ladakh’s economy. Yet, opportunities for educated youth remain limited. Many fear that without statehood or Sixth Schedule protection, outsiders might claim a larger share of government and private jobs.

This anxiety has fueled repeated protests and rallies, where local student groups emphasize the need for exclusive job reservations for Ladakhis. They argue that only such measures can prevent unemployment and out-migration of young talent.

The Balance Between Tourism and Sustainability

Tourism is both a boon and a challenge. Every summer, thousands of visitors flock to Ladakh, boosting local income. However, this seasonal rush strains water resources, increases waste, and puts pressure on the region’s narrow roads and limited facilities.

Locals point out that unregulated tourism could permanently damage the environment and displace traditional livelihoods. They want a sustainable model—one that promotes eco-tourism, supports homestays, and ensures that tourism revenue benefits local communities directly.

Political Mobilization in Ladakh

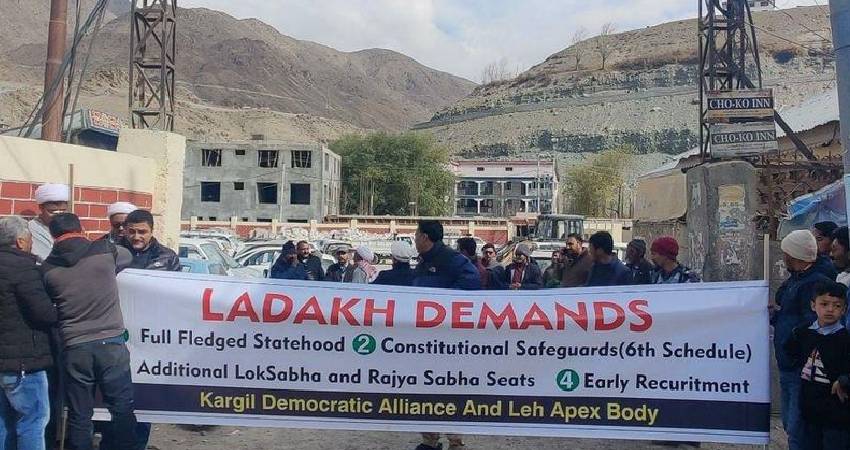

These concerns have led to an unusual unity between Leh and Kargil, which often had different political priorities in the past. The Leh Apex Body and the Kargil Democratic Alliance have come together to demand constitutional safeguards, Sixth Schedule protection, and statehood.

For many Ladakhis, this unity is a rare moment of collective action, showing that the concerns are not just local politics but existential questions about identity, livelihood, and survival.

The Government’s Perspective, Strategic Priorities, and Future Possibilities

Ladakhis are demanding statehood, Sixth Schedule protections, and stronger constitutional safeguards. We examined their fears about cultural dilution, ecological fragility, limited jobs, and the absence of political representation. Yet, to fully understand Ladakh’s position today, it is equally important to examine the government’s perspective. For New Delhi, Ladakh is not just another Union Territory—it is a strategic frontier, a development priority, and a symbol of national integration.

This section dives deep into how the government views Ladakh, the initiatives being undertaken, and the challenges of balancing local demands with national priorities. It also outlines possible roadmaps for ensuring that progress does not come at the cost of culture and ecology.

Why the Government Chose Union Territory Status

When the Government of India announced the abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019 and bifurcated Jammu and Kashmir into two Union Territories, Ladakh’s elevation was framed as a long-pending demand. For decades, leaders in Leh had asked for separation from J&K, arguing that the region’s unique geography and demographics required direct attention from New Delhi.

The creation of the UT was meant to:

- Provide focused governance without the political complexities of J&K.

- Strengthen border security, given Ladakh’s proximity to China and Pakistan.

- Accelerate infrastructure development, which had been slow under the J&K administration.

- Showcase Ladakh as a hub for tourism, renewable energy, and cultural preservation.

From the government’s perspective, UT status ensures direct control and quick decision-making. Unlike a full state, where legislative powers are distributed, a UT allows the Centre to implement policies faster and more efficiently, especially in a sensitive border region.

Strategic Importance of Ladakh

Any conversation about Ladakh must acknowledge its geopolitical significance. Sharing borders with both Pakistan-occupied Gilgit-Baltistan and China’s Xinjiang and Tibet regions, Ladakh is one of India’s most sensitive frontiers.

- The Kargil conflict of 1999 underlined how crucial the region is to India’s security.

- The Galwan clashes of 2020 reminded the world that Ladakh remains at the heart of Indo-China tensions.

- The region hosts some of the Indian Army’s most critical bases, including those supporting the Siachen Glacier.

For the government, therefore, Ladakh is not just about culture and tourism. It is about national security and sovereignty. This explains why the Centre is cautious about devolving too much authority, fearing it could complicate defense and border management.

Development Initiatives by the Government

While Ladakhis raise concerns about political safeguards, the Centre emphasizes the developmental push it has brought to the region. Key initiatives include:

- Infrastructure Expansion

- Construction of all-weather roads like the Zojila tunnel (connecting Ladakh with Srinagar) and the Manali-Leh highway upgrades.

- Air connectivity improvements through the Kushok Bakula Rimpochee Airport in Leh and new heliports in remote areas.

- Renewable Energy Projects

- Plans to develop Ladakh as a hub of solar and wind energy, leveraging its vast open spaces and high solar potential.

- The government has already announced large-scale solar park projects, which, if implemented with sensitivity, could make Ladakh a key contributor to India’s clean energy transition.

- Digital Connectivity

- Expansion of mobile and broadband networks, reducing isolation for villages that were previously cut off for months.

- Tourism Promotion

- Initiatives to brand Ladakh as a global destination for adventure tourism, winter sports, and Buddhist cultural circuits.

- Education and Healthcare

- Establishment of new institutes, colleges, and upgraded hospitals.

- Efforts to provide telemedicine in remote villages.

The government highlights these achievements as proof that UT status allows quicker implementation of projects that would otherwise be delayed under a state assembly.

The Government’s View on Statehood and Sixth Schedule

On the demand for statehood, the government has so far been cautious. Officials argue that:

- A small population spread across a vast geography may not support a full state’s governance structure.

- Direct central rule allows better coordination for security and development.

- Granting statehood could set a precedent that complicates governance in other sensitive regions.

Regarding the Sixth Schedule, the Centre acknowledges Ladakh’s tribal majority but suggests that existing Hill Development Councils (Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council – LAHDC Leh and LAHDC Kargil) already provide representation. Strengthening these councils, rather than introducing a new constitutional framework, has been one of the preferred strategies.

The government’s perspective is that too many restrictions could discourage investment, tourism, and industrial projects. For instance, Sixth Schedule protection might limit private sector participation in renewable energy or tourism infrastructure, areas where the Centre envisions significant growth.

The Balancing Act: People vs. Policy

The real challenge lies in finding the balance between local anxieties and national priorities. Both sides have valid points:

- Ladakhis fear losing control over land, jobs, and identity.

- The government fears that excessive autonomy may hamper national security and economic integration.

This is why dialogue has been the key. Over the past year, the Centre has initiated talks with local groups like the Leh Apex Body and the Kargil Democratic Alliance. While progress has been slow, these talks show that New Delhi recognizes the depth of local concerns.

The Future Roadmap: Possible Solutions

To resolve the current deadlock, several pathways are being discussed by experts, policymakers, and citizen groups.

- Strengthening Hill Councils

- Giving the Leh and Kargil Hill Councils more legislative and financial powers.

- Ensuring that major decisions on land, jobs, and culture require council approval.

- Special Job Reservations

- Introducing legal frameworks that guarantee jobs for locals in government and semi-government institutions.

- Encouraging skill-development programs so that youth can benefit from tourism and renewable energy projects.

- Land Protection Mechanisms

- Implementing laws that restrict outsiders from purchasing agricultural or tribal land, similar to safeguards in Himachal Pradesh and parts of the Northeast.

- Eco-Sensitive Development Policies

- Mandatory environmental impact assessments for all projects.

- Prioritizing eco-tourism and community-driven initiatives over mass-scale resorts.

- Participatory Governance

- Creating consultative bodies that include local leaders, monks, student groups, and women representatives in decision-making.

- Regular town hall meetings between central officials and Ladakhi citizens.

- Cultural Preservation Programs

- Increased funding for monasteries, local crafts, and traditional art forms.

- Inclusion of Ladakhi history and heritage in educational curricula.

Looking Beyond Ladakh: National Development Context

Ladakh’s debate also reflects a larger question facing India: How do you balance development and identity in culturally unique regions? Similar tensions exist in the Northeast, tribal belts of central India, and border states.

The government’s approach in Ladakh will likely serve as a test case for future policies. If it manages to deliver development while preserving culture and ecology, Ladakh could become a model for sensitive governance in frontier regions.

A Shared Vision: Where People and Government Can Meet

Despite differences, one truth remains: both the people of Ladakh and the government want the region to thrive. The path forward will require trust, dialogue, and compromise.

- For locals, it means acknowledging the need for infrastructure, renewable energy, and defense preparedness.

- For the government, it means recognizing that development without safeguards could alienate the very people it seeks to empower.

A balanced roadmap could include limited autonomy with strong safeguards, robust eco-sensitive policies, and guaranteed participation of locals in decision-making.

The Crossroads Moment

Ladakh stands today at a crossroads. Its people want to move forward without losing their past. The government wants to secure the frontier while accelerating progress. Both sides face difficult choices, but also a historic opportunity.

Handled with care, Ladakh could emerge as a shining example of how India balances modernity with tradition, security with democracy, and progress with preservation. Mishandled, it risks becoming a story of alienation in a land that has always been India’s pride.

The stakes, therefore, are far greater than one region—they represent the very essence of national development in harmony with cultural diversity.