India’s welfare state has had a history of layers of administrative chains, subsidized mediation, and departmentally fragmented channels of delivery. The Direct Benefit Transfer System represents a structural departure from that model. Conceived as a governance reform, rather than just a payment mechanism, it is aimed at posing out in-kind and intermediary-driven subsidy flows with digitally authenticated and beneficiary-linked cash transfers. The reform has been presented as a response to leakages, duplication and opacity in public expenditure. However, its long-term implications at the institutional level go beyond the metrics of the efficiency rate. It reconfigures fiscal flows, redistributes administrative authority, and recalibrates center-state relations under the DBT scheme India architecture.

The debate, therefore, is not restricted as to whether DBT ‘saves’ leakage. It concerns whether the Direct Benefit Transfer System enhances systemic efficiency without disproportionately centralizing fiscal and data authority within the Union executive. This article examines the reform from a structural, institutional, and economic perspective.

Policy Context

Pre-DBT Welfare Architecture

Pre-digitized transfers, the welfare delivery in India was based on:

- Identification of physical beneficiary

- Verification process at State Level

- Beneficiary databases specific to Departments

- Subsidy distribution through middle men

- In-kind transfers through public channels of distribution

These arrangements resulted in three continuing inefficiencies:

- Ghost beneficiaries due to poor authentication

- Delays in payments from layered approvals

- Short circuiting money through intermediaries

The Planning Commission, in several internal assessments made in the late ’00s, had pointed to very serious inefficiencies in subsidy administration, especially in the distribution of LPG and fertilizers. This administrative burden became even more severe following the expansion of welfare coverage, in particular after the rights-based legislations such as the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, post-2005.

Read More: National Education Policy 2020 Explained for Competitive Understanding

Development of the DBT Framework

The Direct Benefit Transfer System formally launched in 2013 as a pilot across selected districts. The acceleration that this achieved took place after 2014, which coincided with financial inclusion in a big way under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojna and consolidation of biometric identity under Aadhaar.

The logic behind the structure was simple:

- Unique identity authentication

- Bank account penetration

- Digital payment rails

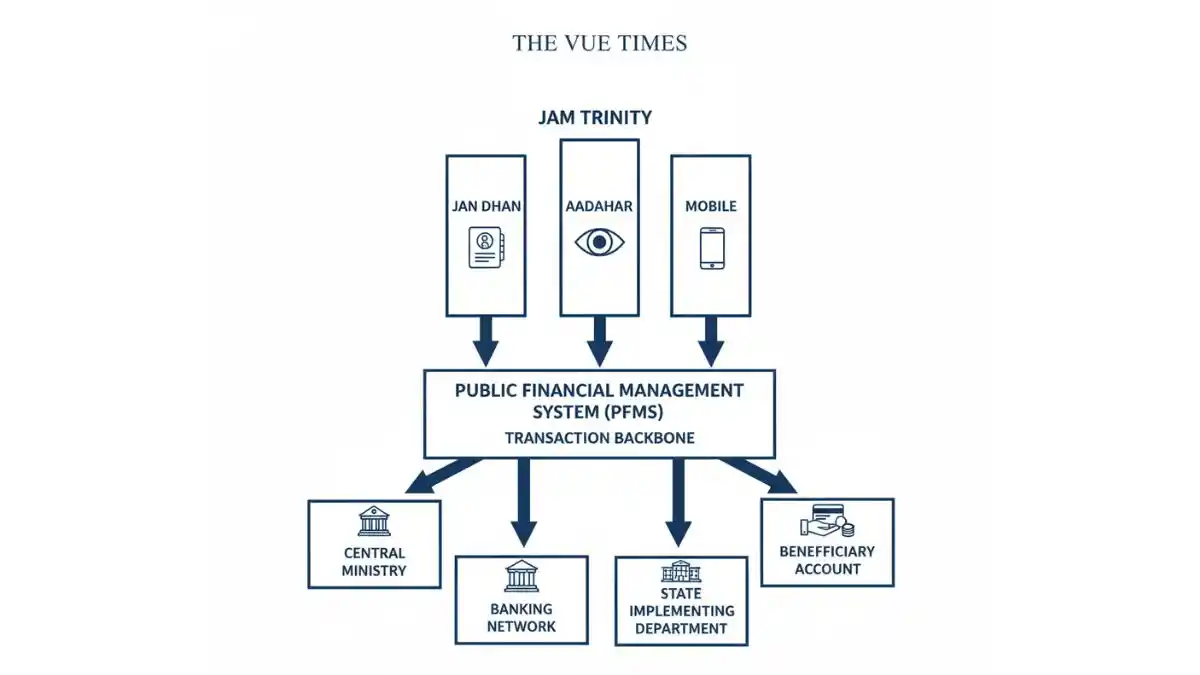

This convergence created what policymakers termed the JAM trinity, Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, and Mobile–forming the infrastructural base of DBT scheme India.

As of 2023, the Government of India has more than 300 schemes under DBT whose cumulative transfer is more than Rs 30Lacore since its inception. This scale positions the Direct Benefit Transfer System as one of the largest digital welfare infrastructures globally.

Institutional Architecture

Direct Benefit Transfer System and Governance Design

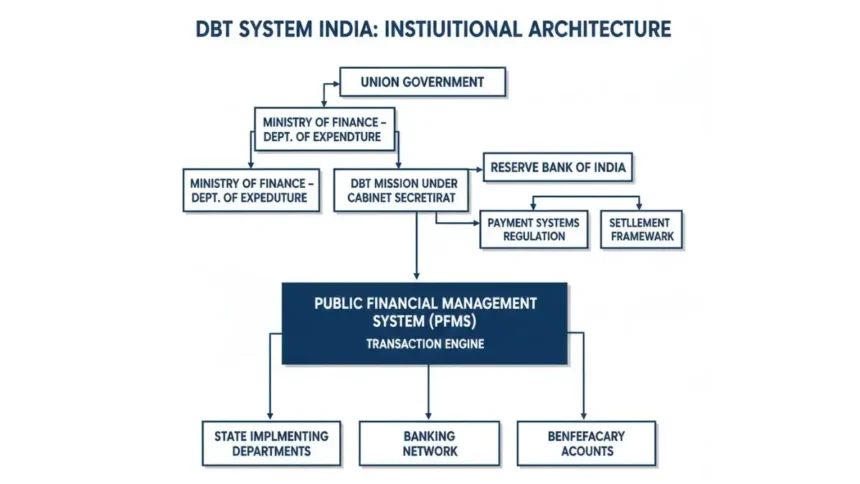

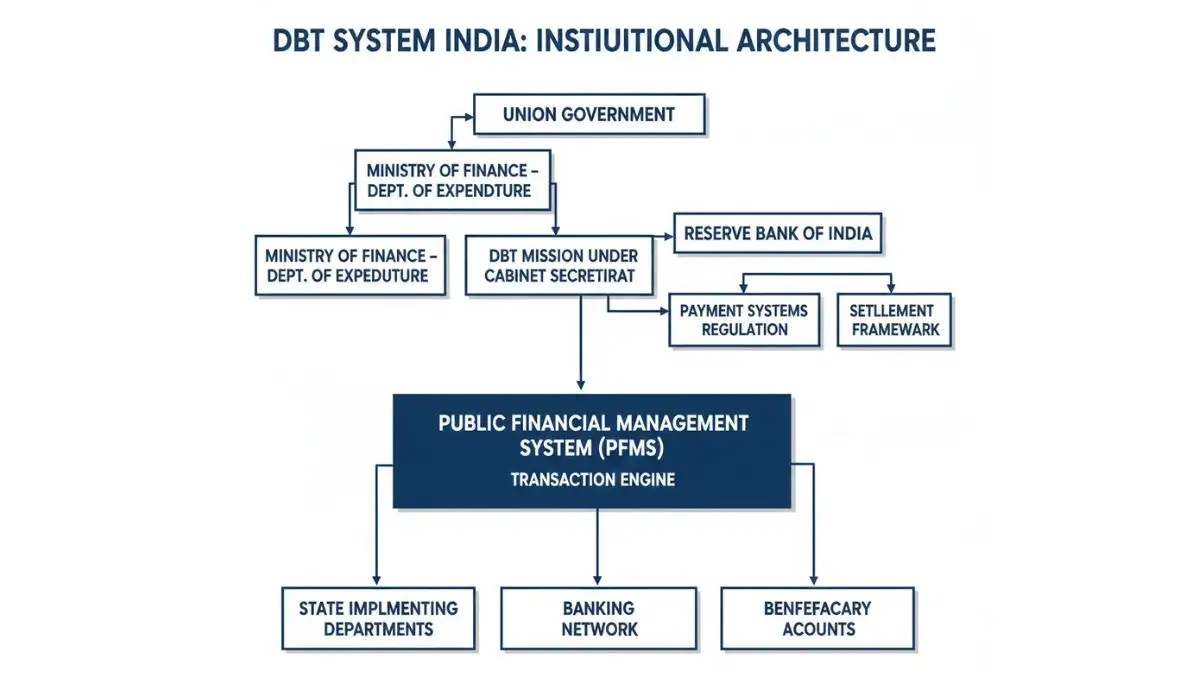

The institutional configuration of DBT is multi-layered across and foundationally based.

Nodal Ministry

The Department of Expenditure under the Min. of Finance is the main coordinating authority. The DBT Mission, which operates under the Cabinet Secretariat, has oversight on the scheme integration, beneficiary validation standard and compliance on digital infrastructure.

The Public Financial Management System operates to serve as the transaction engine at its core. It combines scheme databases and banking systems and allows real-time fund tracking.

Role of Reserve bank of India

The Reserve Bank of India by indirect support to DBT by:

- Regulation of payment systems

- System of Regulating Aadhaar Enabled Payment

- Loss and Damage: Possible frameworks for digital transfer: Settlement

RBI’s payment infrastructure reforms especially under the ambit of National Payments Corporation of India allowed for the interoperability bringing DBT scale. Although RBI does not design welfare policy, its regulatory ecosystem brings back transaction integrity.

Read More: PM Gati Shakti Master Plan: Infrastructure Reform Blueprint

Parliamentary Oversight

DBT-linked schemes are still authorized by regular budgetary processes:

- Demand for Grants

- Appropriation Bills

- Scheme-specific notified by ministries

But once schemes are initiated on the DBT platform, operational flexibility is increased with regard to executive departments. Parliamentary review normally involves analysis of fiscal allocations rather than review of platform governance.

A good institutional cited for in-depth evaluation would include those reports of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India concerning the performance audits on the implementation of DBT in subsidy-heavy sectors.

Federal Implications

The DBT scheme India model creates an asymmetric federal dynamic:

- Centrally sponsored schemes stitch together data from the states at the beneficiary level

- States dependent on central infrastructure on disbursement

- Central ministries control technical and financial control

While the states run numerous schemes, the authentication backbone and financial routing are centralized. This has implications in regards to fiscal autonomy and administrative leverage.

Mechanism and Framework of Operation

Structural Flow

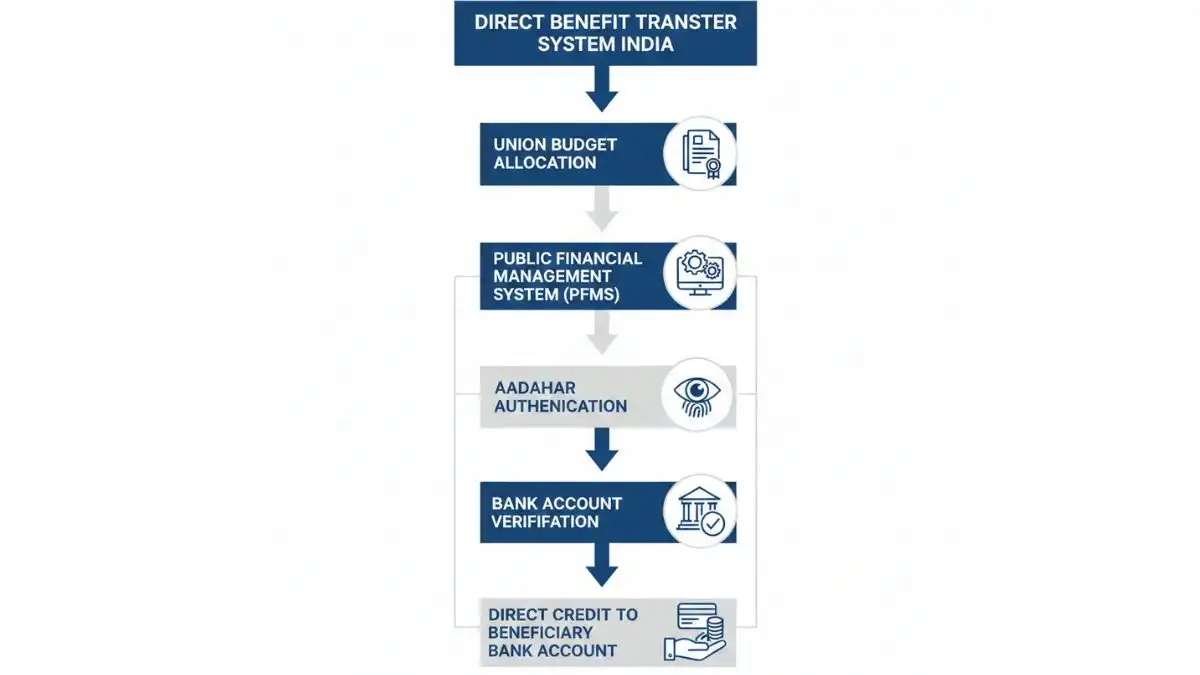

The Direct Benefit Transfer System operates through the following sequence:

- Allocation of funds in Union Budget by Scheme

- Beneficiary identification by implementing department

- Aadhaar authentication

- Bank account seeding

- Fund release through PFMS

- Double credit in beneficiary account

Structural Diagram in Text Format

Policy Allocation – Ministry Sanction – PFMS Integration – Aadhar Authentication – Bank Account Verification – Direct Credit – Transaction Confirmation – Digital Audit Trail

Each node in this chain takes away the intermediary discretion. However, every node also brings dependency to digital infrastructure.

Types of Transfers

DBT covers:

- Cash transfers i.e. PM Kisan

- LPG subsidy under PAHAL

- Scholarship payments

- Wage transfers under MGNREGS

In a number of cases, DBT replaced physical distribution of subsidies. In others, it digitized existing cash disbursement channels.

Real-Time Monitoring

The DBT Bharat Portal publicly displays the coverage of the schemes and volumes of transfers. Of critical importance to the design is traceability, in which the policy makers have the ability to monitor:

- Transaction success rates

- Rejection patterns

- Removal of beneficiary duplication

This data-centric governance model separates DBT from its institutionalized origins in the welfare state of the past.

Economic and Governance Implications

Fiscal Health

The primary economic claim underpinning the Direct Benefit Transfer System is leakage reduction. The government has reported a significant saving of money by removal of duplicate and fake beneficiaries.

Even if there is some debate about the headline saving, DBT has:

- Successful expenditure targeting

- Reduced amount of administrative cost

- Faster budget execution

This helps to have more fiscal predictability and enables reallocating saved funds.

However, fiscal centralization also leads to increase. Funds come from the center and go. Welfare payments are digital, making states less able to sequence discretionary payments.

Federalism

The DBT scheme India framework consolidates welfare visibility at the Union level. While states implement schemes, political attribution comes to the central government easily because of direct beneficiary communication.

This changes the architecture of political accountability:

- Beneficiary perception = central authority

- States may have fiction decreased visibility

From an administrative perspective, there is uniformity. When looked at from a federal perspective, power concentration is even greater.

Administrative Capacity

DBT curtails Man manual processing burdens. However, it creates an increase in demand for:

- Digital literacy

- Data management capacity

- Reconciliation systems / backend systems

District-level administrative jobs move from distributing in the physical to verifying in the digital environment.

Private Sector Linkages

The banking sector is a beneficiary of higher account activity. Payment service providers benefit from scale. Fintech integration grows

At the same time, market competition shrinks where government platforms memories identity authentication and payment routing.

Implementation Gaps

Despite making progress at the seeming systemic level, there are still operational challenges.

Authentication Failures

Biometric mismatch, connectivity problems and Aadhaar seeding errors cause transaction rejections.

Exclusion Risks

People who do not have up-to-date documentation or have access to a bank may experience delays.

Data Governance

Centralized data repositories have raised queries on:

- Data protection standards

- Sharing of data across the ministries

- Consent architecture

India’s evolving data protection regime will play a major role in greatly affecting DBT’s long-term sustainability.

Infrastructure for Banking at the Last Mile

In remote areas, banking correspondent constitutes a cash-withdrawal issue.

As such, digital transfer is not automatically the same as having access.

Criticism and Arguments Against

Criticism: Centralization of Power

Critics say that DBT increases central visibility of fiscal decisions and limits the flexibility for states to operate.

Counter-Argument: Standardization is in favor of accountability, and it also decreases the discretionary leakages.

Criticism: Cash Transfers Substitute Public Goods

Concerns exist about replacing in-kind support systems with cash.

Counter-Argument: Choice is increased by cash transfers, losses are reduced.

Criticism: Digital Divide

The risks of having stakeholders facing digital exclusion include rural and elderly populations.

Counter-Argument: Banking correspondents and models of assisted access minimizes this risk

Balanced evaluation indicates that there are structure risks but they are implementation rather than inherent in the model.

Future Outlook: 5-10 Years

The next phase of the Direct Benefit Transfer System will likely involve:

- Integration with digital public infrastructure frameworks.

- Interoperable state DBT platforms

- Beneficiary analytics using Artificial Intelligence

- Optimization of conditional transfer

Fiscal consolidation pressures could lead to DBT expansion in subsidy usage that has not yet been digitized.

Simultaneously, data governance regulation will establish the limits of the central authority.

If structured carefully, DBT could emerge a transparent, welfare rules-based backbone. If over central it may lessen the cooperative federal equilibrium.

The trajectory used will be by institution balance, not just by technological capability.

Conclusion

The Direct Benefit Transfer System represents a structural transformation in India’s welfare architecture. It improves fiscal traceability and reduces intermediary discretion and enhances transaction efficiency. At the same time, it centralizes financial routing and authentication power using centralized digital infrastructure.

The policy question is not whether the Direct Benefit Transfer System increases efficiency. Evidence suggests it does. The larger question comes from more than mere efficiency gains: are efficiency gains institutionally balanced with federal policymaking autonomy and data governance safeguarding?

As DBT scheme India matures, its sustainability will depend on regulatory refinement, technological resilience, and cooperative federal adaptation. The success of the reform will, however, eventually be measured not only by the fiscal proceeds, but rather by the institutional equilibrium.